On Oct. 10, Korean writer Han Kang was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. The news came as confirmation that Korean literature is no longer only influenced by world literature, but is exerting an influence of its own. Han’s Nobel Prize is a big win for Korea and came together through the convergence of four factors: Han’s creative capability, the power of Korean literature, the talent of her translators and systematic support from the public and private sectors.

Writer. Oh Hyung-yup, Literary Critic

Han Kang’s Creative Capability and Literary Success

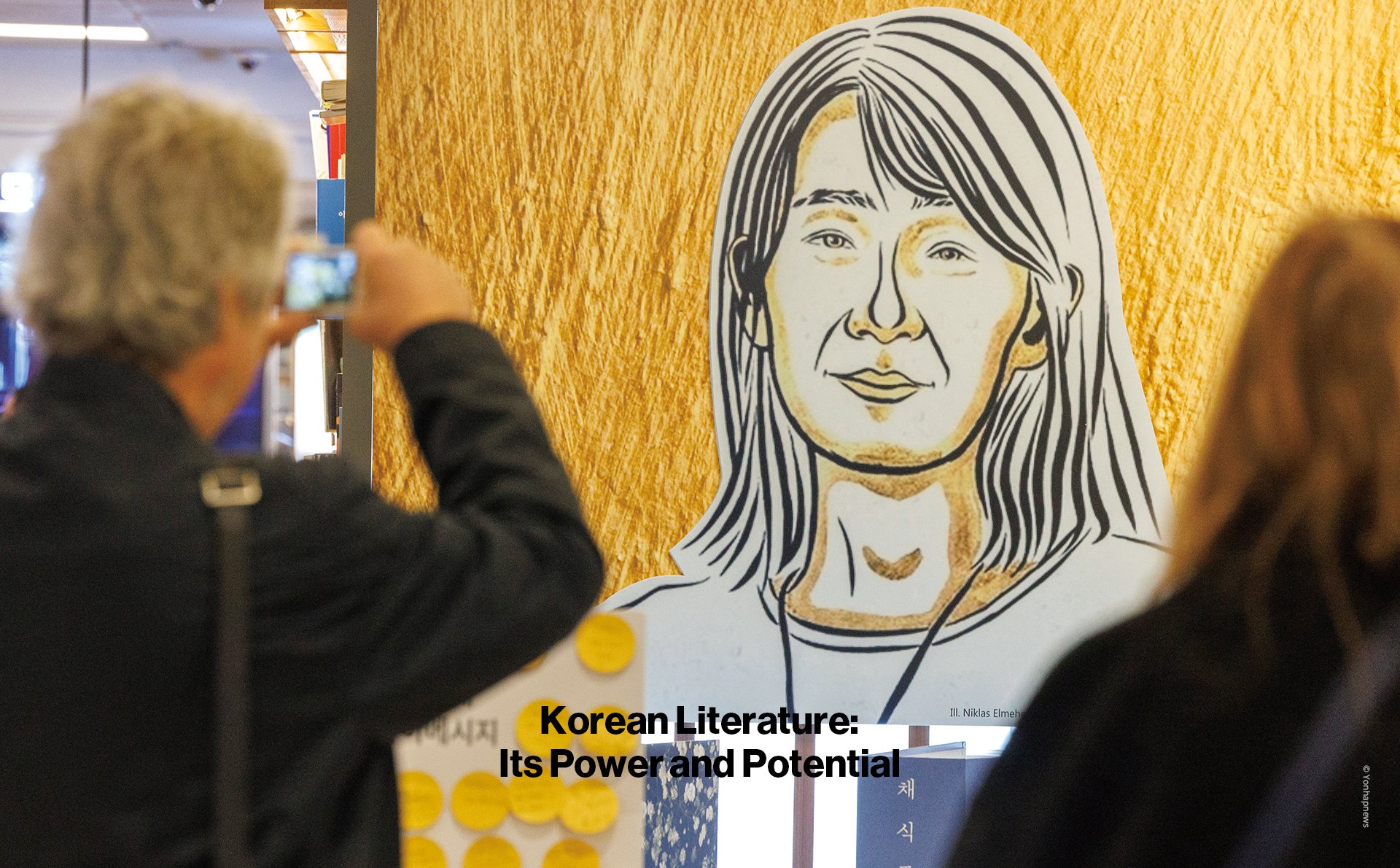

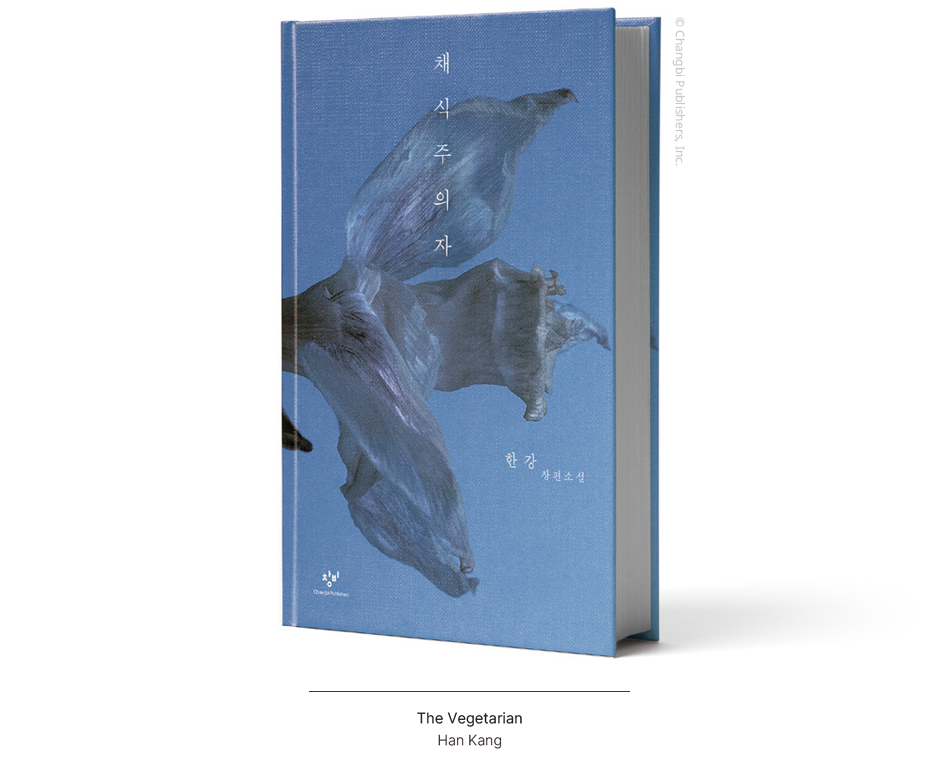

Han Kang’s creative capability is demonstrated in her literary themes, formal experimentation and aesthetic style. In regard to her themes, Han’s novels boldly address the rights of women, the dignity of nature and life, and tragic episodes in Korea’s modern history while seeking to remember and heal that pain and those wounds. She tackles weighty and heavy themes in society and history in such works as “The Vegetarian,” which fuses feminism and ecologism in the body of a woman who dreams of becoming a tree as a way of resisting tradition and patriarchy. Similar characteristics are exhibited in “Human Acts” and “We Do Not Part,” two novels that adopt the language of pain to ease the trauma engendered by the tragedies of the Jeju April 3 Incident and the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement. What sets Han apart as a writer is that she moves beyond the surface level of political and ethical discourse to delve into her characters’ interiority. In so doing, she confronts the violence and barbarism that are part of our human heritage, sublimating those themes into existential questions about the soul and body, love and pain, life and death, and life and the universe.

In terms of formal experimentation, Han’s novels step away from the representational methods of traditional realism and employ a range of aesthetic modes. “The Vegetarian” ventures into a mythical and primeval domain, a kind of fantastical realism that blurs the boundaries of reality and fantasy. The book epitomizes an aesthetic of the grotesque, consisting of shocking characters and unconventional incidents. “Human Acts” adopts a multifaceted perspective that scrutinizes a tragic incident from the perspective of various characters. “We Do Not Part” sets the main character as the observer while fleshing out the story through several connected characters.

As for Han’s aesthetics, her novels have a distinctive poetic style that is at once gentle and placid, yet compact and muscular, with the power to suck readers into the story. Before releasing any fiction, Han had debuted as a poet, publishing a volume of poetry called “I Put the Evening in the Drawer.” That poetic background helps explain the delicate lyricism of her writing. These three disparate elements of theme, form and style collided and combined to bring Han Kang her stunning literary achievement. That achievement is aptly summarized in the Swedish Academy’s statement that it awarded Han with the Nobel Prize “for her intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of human life.”

The Power of Korean Literature and Its Potential for Development

Han Kang’s creative capability was made possible by the power of Korean literature. That power was forged from the legacy of classical literature and the impact of Western literature during the late 19th and 20th centuries, undergoing creative permutations to elevate Korean literature to new and unprecedented heights. As a writer, Han Kang cultivated her talents and drew inspiration from the brilliant works in the Korean literary canon. Then, she channeled those influences into her own literary world, which ultimately led to her winning the Nobel Prize.

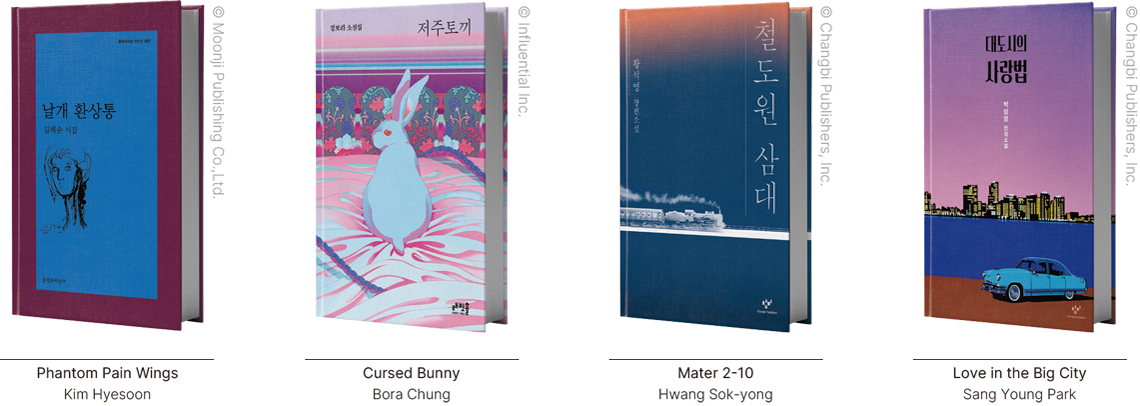

Drawing upon this wellspring of power, Korean literature has a potential for development that became tangible as Korean literary works began picking up a range of international literary awards in the 2010s. Korean literature’s debut on the stage of global literature was signaled by Han’s novel “The Vegetarian” being awarded the Man Booker International Prize in 2016. Since then, Korean books have become regular contenders for international literary prizes. “Autobiography of Death” by the poet Kim Hyesoon won Canada’s Griffin Poetry Prize in 2019. In addition, a flurry of Korean novels have been considered for the International Booker Prize in recent years: “The White Book” by Han Kang on the shortlist in 2018, “Cursed Bunny” by Bora Chung on the shortlist and “Love in the Big City” by Sang Young Park on the longlist in 2022, “Whale” by Cheon Myeong-kwan on the shortlist in 2023, and “Mater 2-10” by Hwang Sok-yong on the shortlist in 2024.

In 2023, Han Kang’s novel “We Do Not Part” (translated into French as Impossibles adieux) received France’s Prix Medicis award for foreign literature, and in 2024, Kim Hyesoon’s book “Phantom Pain Wings” was given the poetry honor in the National Book Critics Circle Awards. Kim Hyesoon’s poetry has raised awareness of contemporary Korean poetry’s outstanding artistry and aesthetic quality in the American literary world, opening up new horizons for the genre. In addition, the Japanese translation of Cho Nam-joo’s novel “Kim Ji Young, Born 1982” has sold more than 200,000 copies since its publication, becoming a favorite of young women readers. Indeed, the novel has become a touchstone for dialogue about feminism in Japanese society. Korean literature has continued to stack up international plaudits, with Han’s selection for the Nobel Prize representing the zenith of that process.

The Talent of the Translator, Support from Public and Private Sectors

A massive factor behind Han winning the Nobel Prize was the power of translation, which can be seen as a collaboration between the ability of individual translators and the concerted support of the public and private sectors. In regard to the talent of the translator, mention must be made of the contributions of British translator Deborah Smith. The New York Times included her translation of Han’s novel “The Vegetarian” on its list of the 10 Best Books of 2016, remarking that “this spare and elegant translation renders the original Korean in pointed and vivid English.” After translating “The Vegetarian,” Smith continued with other novels by Han, including “Human Acts,” “The White Book” and “Greek Lessons.” As mentioned earlier, “The White Book” was selected for the shortlist of the International Booker Prize in 2018, reconfirming the importance of the translator’s ability.

Credit should also be given to unflagging support for translation from the public and private sectors. That includes translation grants aimed at the “globalization of Korean literature” that has been steadily provided by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea), established under the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism in 1995, and by the Daesan Foundation, launched by Kyobo Life Insurance in 1992. Through grants from LTI Korea, all of Han’s works, including and following “The Vegetarian,” have been translated into 28 languages―such as French, Vietnamese and Spanish―and published 76 times worldwide. These two organizations alone are said to have helped fund the publication of 2,600 of 3,000 Korean books released overseas since they began systematically supporting the translation of Korean literature. That statistic underlines the critical role that institutional support has played in translation.

Tasks for the Future: Promoting Criticism and Translation

Since the Korean wave took off in the 2000s, Korean popular culture, including films, dramas, pop music and webtoons―often known by the shorthand of “K-content”―has exerted a massive impact on the whole world. While Korean literature has often been the under-appreciated inspiration of K-content, it now needs to grow and develop while creating synergy with K-content. That growth and development will require even more interest and investment on an individual, private and public level as we prepare for the future. There is a particularly urgent need for efforts to stimulate the ecosystem for Korean literature and promote its healthy development at home, while continuing to promote translation to facilitate its transmission overseas.

What are some specific ways we can help Korean literature grow and develop alongside K-content? First, we need to promote a “critical discourse” in the interest of centering Korean literature and cementing its position. Second, we need to promote the translation of Korean literature for the goal of its transmission and dissemination. A consensus about the need to promote translation has been forming in Korean society since Han won the Nobel Prize. The promotion of a critical discourse basically entails a two-pronged strategy of first fostering criticism in Korea and then spreading it overseas. Fostering literary criticism at home demands our interest and support because such criticism is essential if the Korean literary ecosystem is to both survive and thrive. In addition, the translation of literary criticism should be linked to the translation of literary works as a way of actively supporting the transmission of that criticism overseas. Thus, it is important that we establish a cycle consisting of the following steps: creation of literary works, production of a critical discourse, translation of literature and criticism and transmission overseas.