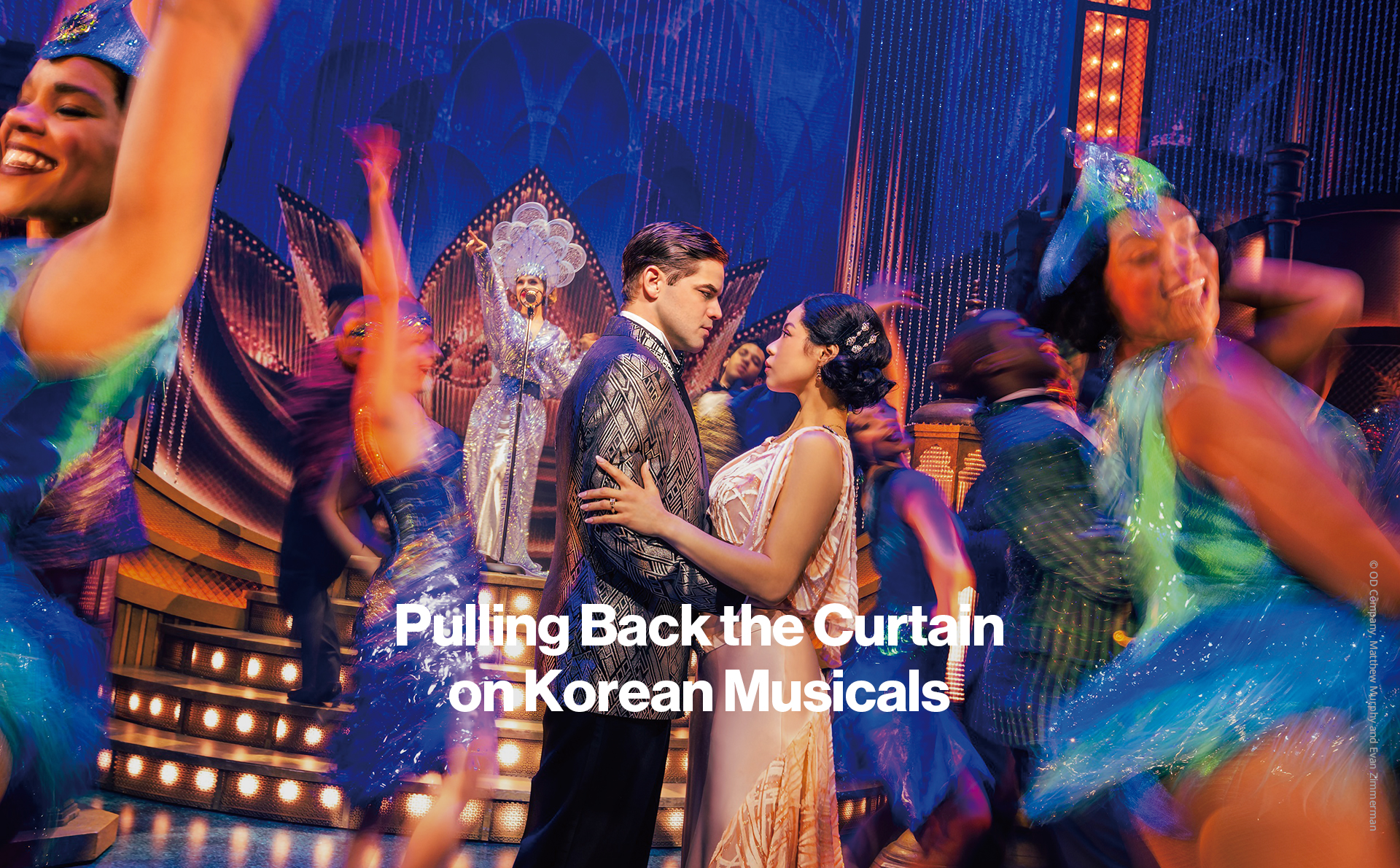

This summer, I sat in the audience at the Broadway Theatre in New York, waiting for the curtain to rise for the musical “The Great Gatsby.” A Caucasian woman in her early 60s seated beside me turned and said, “You know, I just love this show! This is my fifth time to see it.” I replied, “That’s incredible! This show was produced by a Korean.” “I know!” she said. What is it about “The Great Gatsby”―and other Korean musicals―that has enchanted the lady sitting next to me and so many others?

Writer. Choi Seungyoun

Korean Musicals: Past and Present

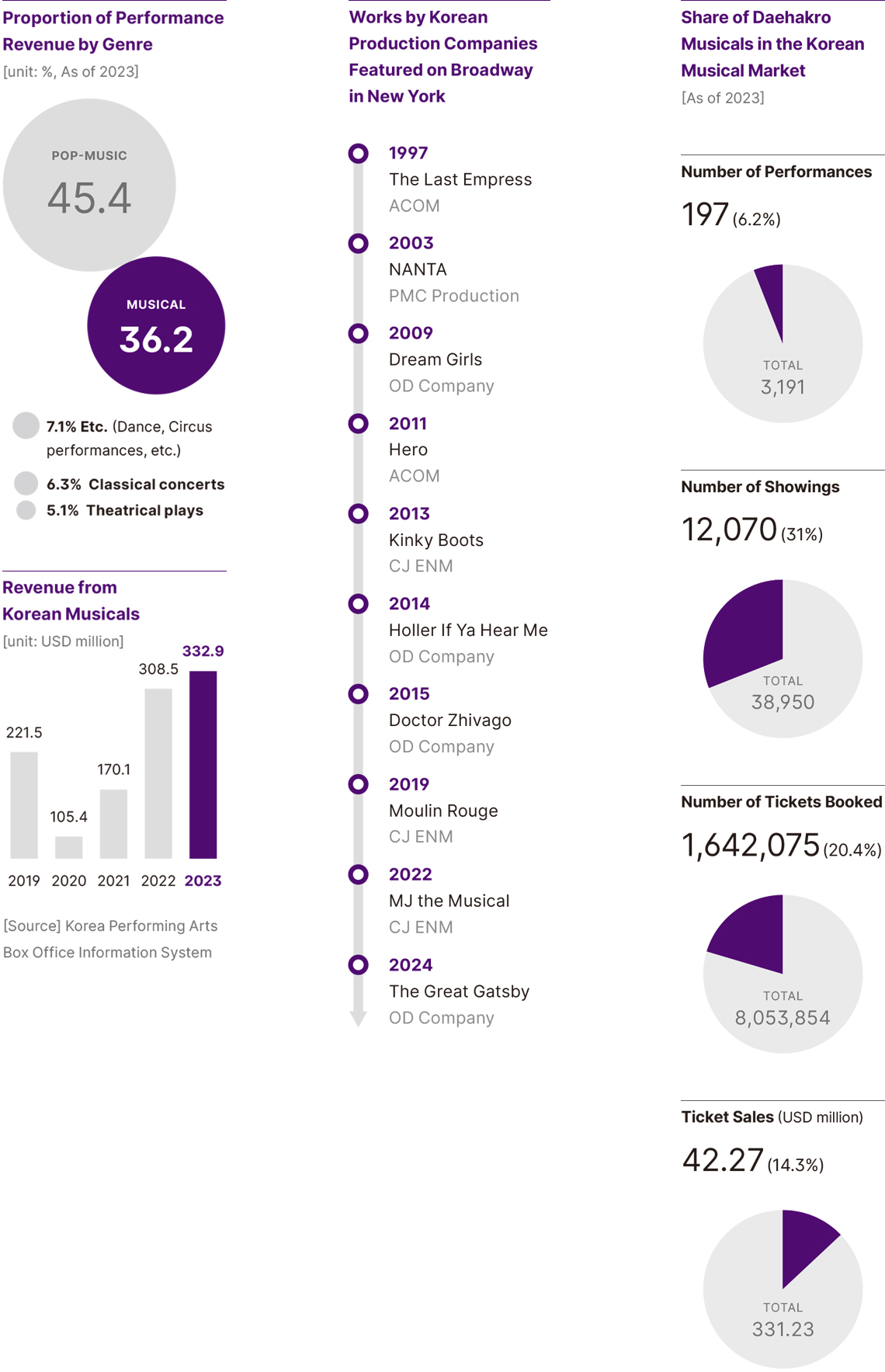

In 2023, Korean musicals brought in a total of KRW 459 billion (about USD 332.9 million) in ticket receipts. Industry sales were up 8% from the previous year, representing 3,178% growth since the Korean musical industry took off in 2001 (with KRW 14 billion in sales). The biggest driver of success was overseas musicals licensed for performance in Korea. The “Phantom of the Opera,” which was staged for seven months in 2001 and 2002, earned around KRW 20 billion, intimating the potential of the domestic musical industry. After “Chicago” and “Rent” set things in motion in 2000, musicals that played a decisive role in expanding the market included “Jekyll & Hyde” (2004), “Mozart!” (2010) and “Kinky Boots” (2014), among others. These guaranteed hits were produced by several production companies that emerged around this period, such as Seensee Company, Seol & Company (now S&Co), OD Company, Shownote, CJ ENM and EMK Musical Company.

But from an early time, there has been a strong desire in the industry for original Korean musicals. That desire has made the market especially resilient. The country’s first homegrown musical, titled “Sweet Come to Me,” was staged in 1966. Decades later, local production company ACOM (established in 1993) came out with “The Last Empress” (1995) and “Hero” (2009), historical musicals for the big stage that continue to pack auditoriums today.

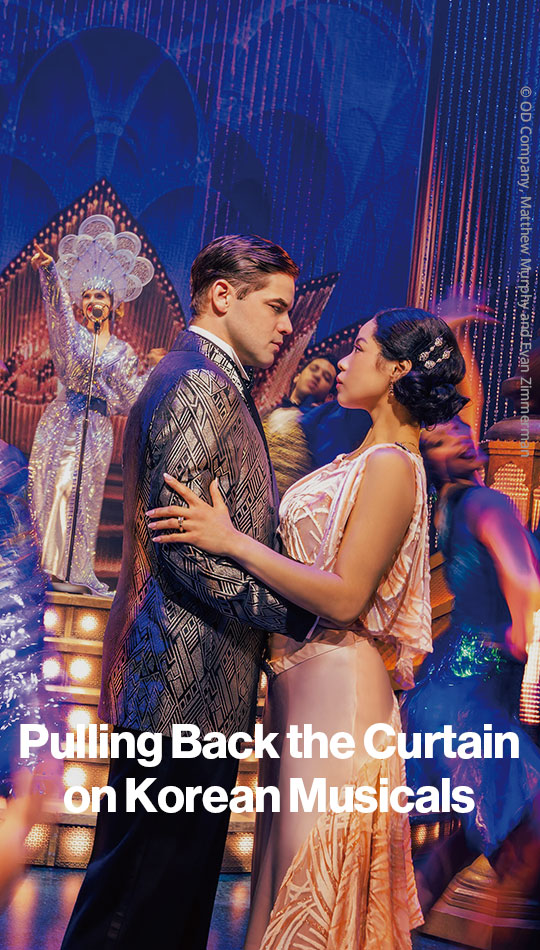

The musical <Dracula> © OD Company.

The musical <Dracula> © OD Company.

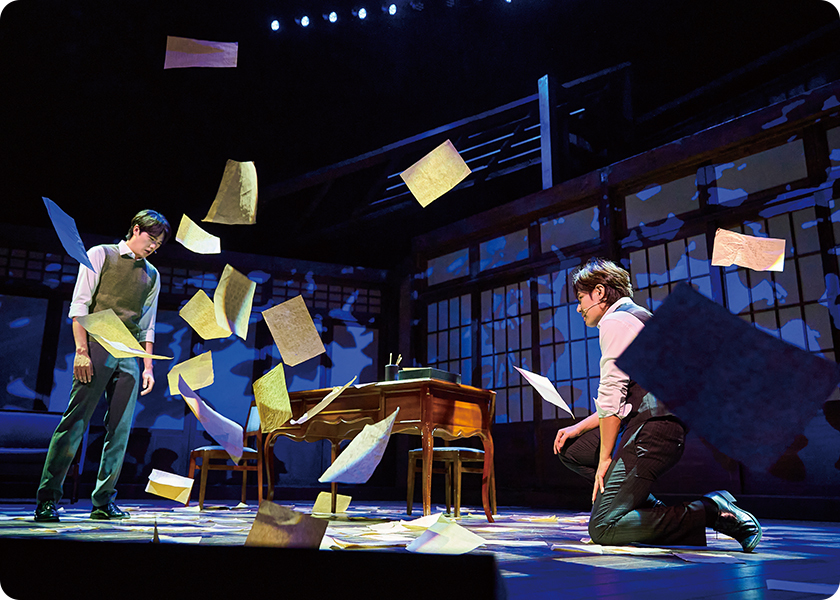

The musical “Line 1,” adapted from a German production, was performed 4,257 times after its debut in 1994, becoming one of Korea’s definitive musicals. “Frankenstein” premiered in 2014 as part of a significant effort to shift Korean musicals away from topics of local interest, such as traditions and history. “Il Tenore” (2023), inspired by the true story of Lee In-sun, Korea’s first operatic tenor, features an opera-within-the-musical, marking a major expansion of the genre’s artistic scope.

Another notable feature in the development of Korean musicals is that small-and medium-sized theaters in the district of Daehakro of Seoul have been picking up work by up-and-coming creative teams. These teams, which began to appear in 2010, have contributed to the diversification of Korean musicals. Another major contributor is a government program for subsidizing original musicals launched around that time. Daehakro theaters ended up hosting a series of smash hits that grabbed viewers by the lapels. Prominent among these are “The Goddess Is Watching” (2013), “Fan Letter” (2016), “Hope” (2019) and “Who Lives in the Kuroi Mansion?” (2021).

Looking back at the history of the Korean musical market, one of the world’s four biggest markets today, we can see the combined influence of the invigorating impression made by foreign musicals and the industry’s longstanding desire to put a uniquely Korean spin on musicals. Licensing popular musicals from abroad provided experience in new methods of creation and production, and the gradual accumulation of overall market experience facilitated an understanding of how musicals are built on plots and numbers. That experience and knowledge, combined with Korean musical viewers’ particular tastes, help musical practitioners stay abreast of the latest industry developments.

Korea’s Musicals Play Up Their Korean Identity

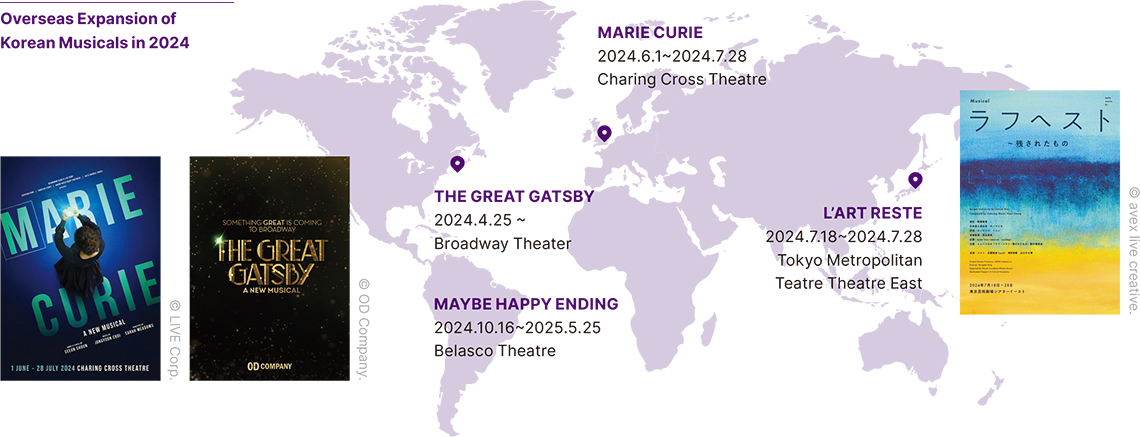

Those trends led to a historic turning point in 2024, particularly in global business. The first Korean musical exported abroad was “Love in the Rain,” staged in Japan in 2008. Other exports included “Finding Mr. Destiny” (China, 2013) and “Fan Letter” (Taiwan, 2018). Although political disputes once hampered efforts to expand into East Asia, today progress is being made in both IP exports and cultural exchange.

One noteworthy trend is Korean musicals’ growing presence in the Anglo-American market. In fact, that is the culmination of efforts that trace back to the 1980s. “Tale of a Nobleman” was performed in five cities in the western United States in 1987, while “The Last Empress” was repeatedly shown overseas in New York (1997), Los Angeles (1998), London (2002) and Toronto (2004). But strictly speaking, overseas performances in that era did not represent expansion into the overseas market. Those shows were either part of state-organized events or were aimed at raising awareness on Broadway and the West End. However, the Korean musicals that reached the Anglo-American market in 2024 are the product of a more business-minded reading of local audiences’ tastes and desires. “The Great Gatsby” was brought to Broadway by OD Company head Shin Chunsoo as sole producer, “Marie Curie” (by LIVE Corp.) was staged from June to late July at Charing Cross Theatre, and “Maybe Happy Ending” by Will Aronson and Hue Park began performances at the Belasco Theatre on Broadway in October.

The tremendous potential that Korean musicals are demonstrating on the international stage can be explained in three ways. First, the Korean musical industry has consistently attempted to extend beyond Korea’s local market. After the Korean musical market gained a devoted following among women in their 20s and 30s, the industry constantly sought to expand overseas while maintaining the support of local fans. “Universality” was a critical element in making that a reality. Some of the signature characteristics of Korean musicals today are themes of human love, desire and agency and numbers with dramatic and dark melodies. Those characteristics are particularly sought after in Japan, as illustrated by “Frankenstein” (2017), which was co-produced by Toho and Horipro, and “Mata Hari” at the Moulin Rouge (2018), which was put on by the Umeda Arts Theater. “The Great Gatsby,” which is taking Broadway by storm, can be explained in a similar context. The show’s universal appeal derives from its bright and lively style, which is tailored to Broadway watchers’ interest in humor and humanism. Simultaneously, it neatly synthesizes the source novel’s musings on the American dream in the form of Jay Gatsby’s love for Daisy Buchanan.

Second, there is clear evidence that Korean musicals, particularly those staged at the small and medium-sized theaters of Daehakro, the mecca of Korean musicals, are gaining a passionate following in East Asia. China, for example, has been importing Daehakro musicals that rely on multiple viewings by loyal fans, including “Mia Famiglia” (2020, Focustage), “Mio Fratello” (2021, Focustage), and “Vanishing” (2023, Salute). This is breathing new life into China’s rapidly growing domestic market. A defining feature of Daehakro musicals is how they deepen dark and ambiguous scenes through songs in a minor key, making their full impact unfold over repeat viewings―a strategy well-suited to expanding the Chinese market. It’s no coincidence that elements of Daehakro musicals appeared in “The Butterfly on the Bund 1939,” the first Chinese musical licensed for production in Korea.

Third, Korea has become a country with multiple hit musicals of its own, positioning it as an all-in-one musical marketplace for East Asia and a supplier of high-concept media for the Anglo-American market. The vision of establishing an integrated musical market for East Asia is gradually becoming more tangible. For example, the musical “Oz” was created by a Korean team in collaboration with the Korean branch of Japan’s production company Amuse. Japan’s Horipro is working with Korean creatives to adapt “Misaeng: Incomplete Life” into a musical. Chinese production company Focustage has collaborated with Korean teams since “The Butterfly on the Bund 1939.” Recently, “Marie Curie” in London highlighted diversity through the physicist’s struggles in a male-dominated field, and “Maybe Happy Ending,” slated for Broadway, debuted a new vocal technique.

Marie Curie by LIVE Corp © LIVE Corp.

Marie Curie by LIVE Corp © LIVE Corp. Fan Letter by LIVE Corp © LIVE Corp.

Fan Letter by LIVE Corp © LIVE Corp.Korean Musicals:

What Lies Ahead

In 2022 and 2023, Broadway posted total sales of USD 1.5 billion, about four times the size of the Korean market. Nevertheless, Korea has been building a competitive musical market by acquiring expertise in original musicals and constantly branching out and trying new things. The 60-year history of Korean musicals proves that. The private-public musical subsidy system established in 2010, growing support for musical globalization from the Korea Arts Management Service since 2020, and the breathtaking talents of actors and passion of producers and creators that are growing every day―all of these kindle expectations about the future of Korean musicals. In short, the day of Korean musicals has finally arrived.

Writer. Choi Seungyoun

Musical Columnist

Choi is a musical critic with a doctorate from Korea University. She fell in love with musicals while watching “The Sound of Music” as an elementary school student and has been studying and enjoying musicals ever since.