Myeongtae (pollack) is one of the most popular fish in Korea. While it is sometimes eaten fresh, dried varieties, including highly prized frozen-thawed preparations known as hwangtae, are specialties that can be enjoyed all year round—in a seemingly endless number of dishes.

Writer. Tim Alper

If you travel around the scenic Gangwon State (Gangwon-do Province) of Korea during the winter months, you could be forgiven for thinking you are in Scandinavia. The terrain is often rugged, mountainous and snow-covered. But that is not the only similarity: almost everywhere you go, you will see rows of large pollack, known as myeongtae, drying on wooden frames.

Indeed, gourmet travelers travel the length and breadth of the country to come to Gangwon-do to sample or buy this fish. Known as hwangtae, it is painstakingly prepared by repeatedly freezing and thawing whole fish outdoors on frames over the course of up to 90 days.

(Left) Saengtaejjigae, a stew made with saengtae, which refers to freshly caught myeongtae © TongRo Images Inc.

(Left) Saengtaejjigae, a stew made with saengtae, which refers to freshly caught myeongtae © TongRo Images Inc.

(Right) Myeongtaejeon, pollack coated with egg and flour and pan-fried in oil © TongRo Images Inc.

The famously windy and cold Gangwon-do winter climate is perfect for preparing hwangtae. Known for its uniquely rich flavor, distinctive yellow hue and unmistakable texture, it is often enjoyed in hwangtaeguk. This rich, warming soup is made with rehydrated hwangtae, simmered with vegetables. The dish is a Gangwon-do specialty, but is now eaten all over the country, where many swear by its efficacy as a hangover cure.

A dish of myeongtaesikhae (salted and fermented pollack) served over bibimnaengmyeon (spicy buckwheat noodles) © TongRo Images Inc.

A dish of myeongtaesikhae (salted and fermented pollack) served over bibimnaengmyeon (spicy buckwheat noodles) © TongRo Images Inc.

However, hwangtae is just the tip of the Korean myeongtae iceberg (albeit a very icy one!). Myeongtae thrive in cold sea waters. Adult fish are found most frequently in waters that do not rise above about 10 ºC. As the heat of summer begins to intensify, they migrate to cold waters, preferring to spawn in even cooler areas. As such, the waters that wash the coasts near Gangneung, averaging at about 8 ℃ in January, make perfecthunting grounds for myeongtae fishing crews.

The East Sea remains an important fishing location for myeongtae, although much of Korea’s myeongtae is now imported. The Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries believes that the average Korean consumes 2.67 kg of myeongtae per year.

But if you look at the way Koreans eat this fish, that statistic becomes less surprising. While many global cooks discard pollack roe and intestines, Koreans are careful not to discard these ingredients. The intestines are typically salted, fermented and sometimes seasoned with spicy pepper powder. This preparation is often used as an ingredient in other dishes or as a base for stews. But it is also eaten as an accompaniment to steamed rice-based meals.

The scene of making hwangtae by drying pollack’s moisture in winter Gangwon-do © TongRo Images Inc.

The scene of making hwangtae by drying pollack’s moisture in winter Gangwon-do © TongRo Images Inc.

Pollack roe, called myeongnan in Korea, is highly prized, meanwhile, and treated with the utmost care during preparation, so as not to rupture the delicate membranes that hold the many eggs together. Cooks typically preserve the sacs in salt for a few days to firm them up before rinsing in salt water. These are then later seasoned with red pepper powder.

Preserved myeongnan is then either cooked in a stew with myeongtae intestines to make a spicy and highly nourishing preparation called altang (spicy fish roe soup) or served uncooked, coated in a few drops of sesame oil, making for a pleasantly salty accompaniment to a bowl of plain rice.

Myeongnanjeot (salted pollack roe) with rice © Gettyimages Korea.

Myeongnanjeot (salted pollack roe) with rice © Gettyimages Korea.

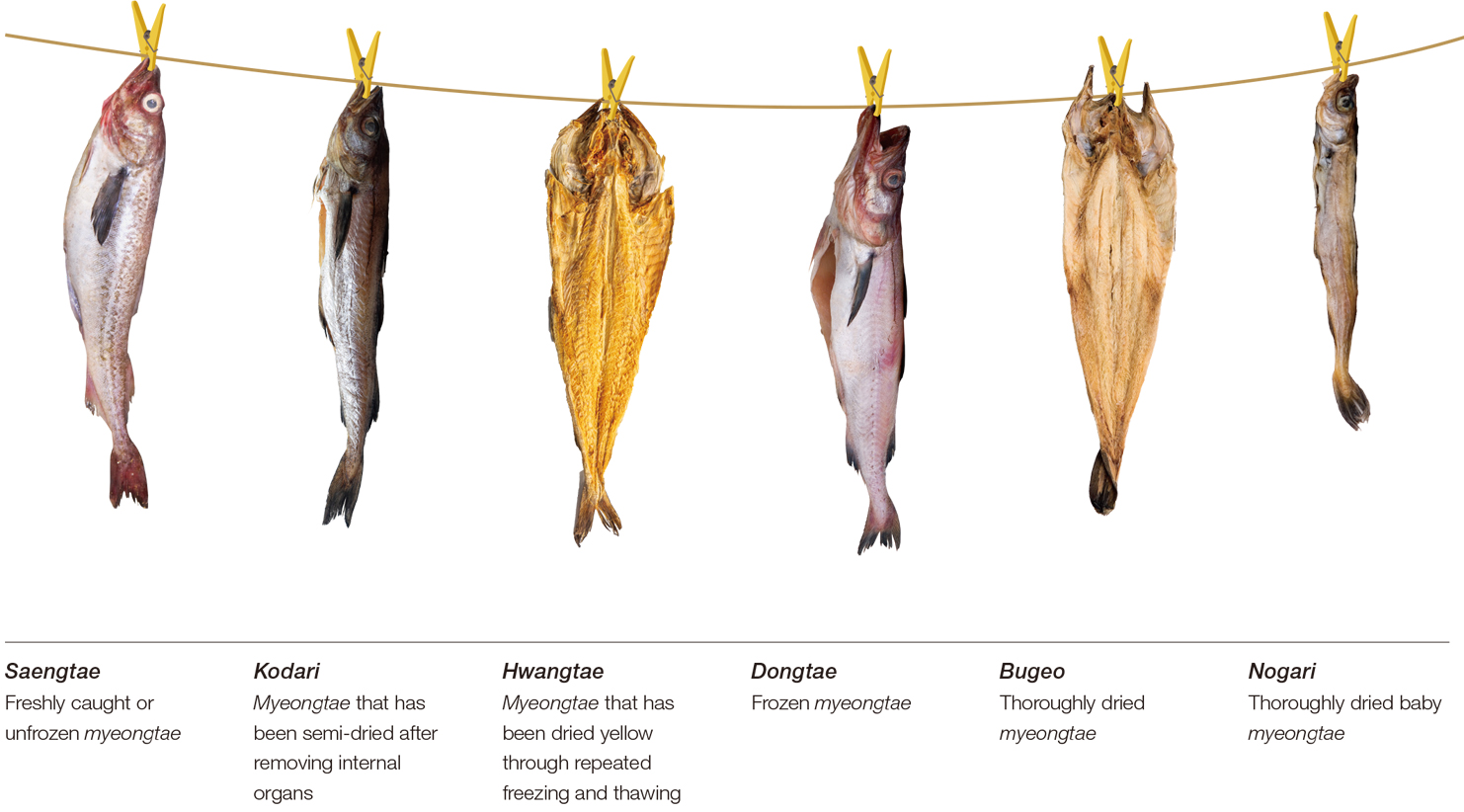

As well as scores of salted, fermented and dried preparations, myeongtae is also eaten freshly caught, where its texture is—by contrast—softer, and its flavors more delicate. However, the fact that myeongtae has over two dozen names in Korea, so many of which denote a different preservation method, should serve as a clue to the more alert of culinary sleuths.

Fresh fish spoils very quickly, and without modern tools like refrigerators and freezers, it would often become inedible just hours after fishing crews returned to shore. But salt preservation and drying techniques allowed cooks to sidestep these concerns.

Koreans began to experiment with different ways to preserve their precious catch, and used the elements to their advantage. The repeated cycles of freezing and thawing myeongtae is no mere tradition. The time-consuming process allows tiny ice crystals to form in the fish’s flesh, breaking down otherwise tough strands of protein. This method does not just radically improve myeongtae’s shelf life. It also bestows the resulting hwangtae with a tenderness that conventional drying methods simply cannot replicate.

So flavorful and tender is the resulting product that you can eat it as-is. And Koreans often do just that. Roughly torn strands of hwangtae make a perfect snack for beer drinkers on a hot day, with some drinkers dipping their fish in a smear of mayonnaise.

Various forms of hwangtae, meanwhile, are also used to make jeon: a kind of pan-fried fritter made with an egg-based batter. This is both a lunch box favorite and a dish commonly served at the jesa, a traditional ceremony held in honor of deceased relatives. Similar ingredients are used to make bugeotguk (dried pollack soup), a popular soup made with rehydrated myeongtae dried using more conventional methods. Other types of white fish are also popular in Korea, including the more elusive and expensive cod. However, myeongtae’s more affordable cost and greater availability make it a far more popular and accessible alternative. Even foreign visitors who are not so keen on briny seafood and fishy flavors find it hard to resist Korean myeongtae’s mesmerizing, mild taste—and seemingly infinite variety.

Snacks imitating the taste of nogari (dried baby pollack) or

Snacks imitating the taste of nogari (dried baby pollack) or  Meoktae, with its crispy yet subtly chewy texture, as well as hwangtae,

Meoktae, with its crispy yet subtly chewy texture, as well as hwangtae, Hwangtae, 1 Tbsp ganjang (soy sauce) 1 Tbsp corn syrup, 1 Tbsp gochujang (red chili paste), 1/2 Tbsp red pepper powder, 1 Tbsp sugar, 1 tsp minced garlic, 1 Tbsp sesame oil, 1 stalk green onion, a pinch of toasted sesame seeds