Hanok, the traditional houses of Korea, come in a variety of forms, serving as palaces, temples and private homes, while incorporating the same underlying philosophy, architectural techniques and spatial arrangement. Their compositional harmony, and the comfort it creates continue to win people’s hearts in the modern day.

궁궐, 사찰, 민가 등 한국 전통 가옥의 모습은 달라도, 그것에 깃든 철학과 기술, 공간 구성 방식은 한결 같다 .이들이 조화를 이루며 만든 넉넉함은, 오늘날 우리의 마음을 다시금 끌어당긴다.

Writer. Lee Kwan Jick

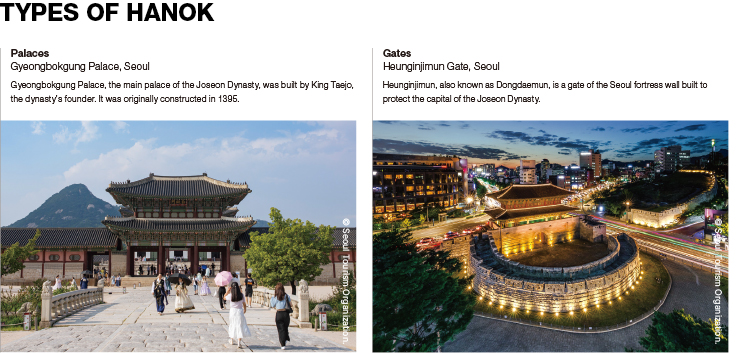

Hanok are traditional Korean houses built as multipurpose wooden structures with tile roofs. Hanok occupied a central place in the daily lives of every Korean, from the lowliest commoner to the king himself. The palaces and walls of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) in Seoul encapsulate the finest architectural techniques of their time.

Hanok also played an intimate role in the lives of ordinary Koreans. The style is witnessed in the buildings dotting Buddhist temple complexes and in the traditional villages that formed around the country in the Joseon Dynasty. Seonbi (scholar-gentlemen) often built gardens and cottages for study and contemplation.

© Korea Tourism Organization.

© Korea Tourism Organization.

Seongyojang House, Gangneung, Gangwon State (Gangwon-do Province)

Seongyojang was the house of a high official of the Joseon Dynasty. The anchae (women’s quarters) was built in the early 1700s by Yi Nae-beon.

The Hanok style is rooted in neo-Confucian thought, which was the ruling ideology of the Joseon Dynasty. It was also incorporated into architecture, becoming the criterion for dividing spaces and determining size, form and proportion, depending on the status of the intended user.

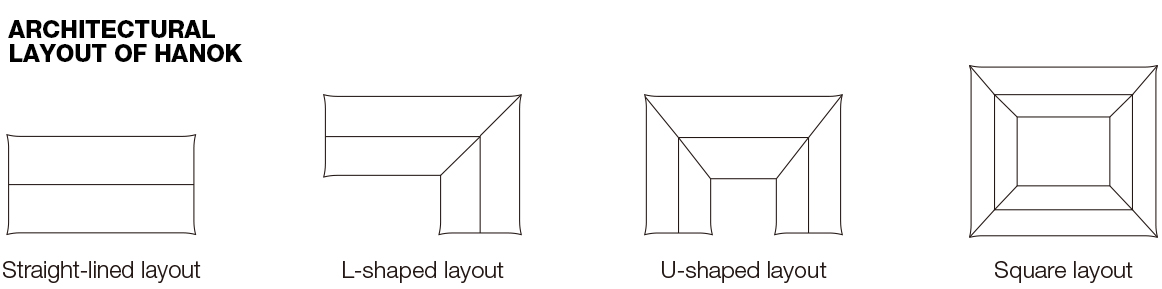

Hanok are divided into separate structures known as anchae, sarangchae and haengnangchae. The anchae housed the mistress of the house, while the sarangchae was where the master studied, relaxed and entertained guests. The haengnangchae contained the servants’ quarters, the stable, the storehouse and the main entrance. Each unit featured a main hall or porch called a maru, with rooms of varying size arranged around a courtyard, the madang. The number of rooms depended on the family’s size and wealth, and the structures were typically linear in layout or shaped like an L, U or square.

Hanok also made full use of the natural terrain to create hierarchical spaces. The outer yard, at the same level as the road, was used for tasks such as grain threshing and other collective work. Facing this yard was a stone platform that supported the haengnangchae and the main gate, which opened into the square inner yard. The primary space of the anchae was an open wooden hall called the daecheong-maru, from which one could look over the inner yard as well as the lower outer yard through the main gate.

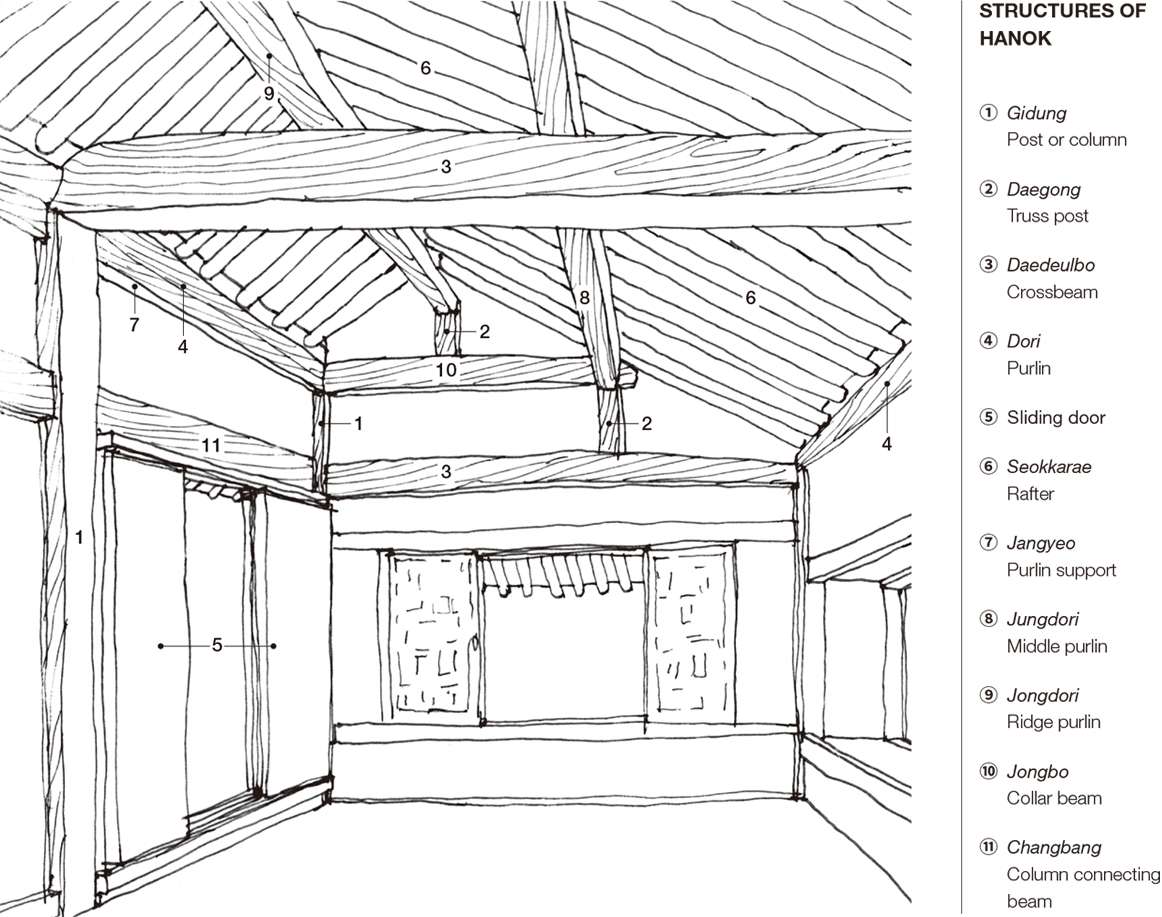

Hanok are traditional Korean houses made mainly of wood, with visible posts and beams forming the structure. Foundation stones (juchutdol) are laid first to support the wooden posts. Between the posts, long purlins (dori) are set, and large crossbeams (daedeulbo) are placed across them. At the center, a short post supports the ridge purlin (jongdori), creating a triangular roof frame. Rafters (seokkarae) extend from the ridge down toward the posts, then are covered with wooden planks or bamboo and a layer of earth. Finally, rows of roof tiles (giwa) are added to complete the roof.

Hanok counter lateral force with the sheer weight of its roof, which descends in a graceful curve. The long wooden roof beams, fixed at both ends, naturally sag in the middle like a suspended rope, while the rafters supporting the roof fan outward, with their tips rising slightly.

Hanok are plainer inside than outside. The walls are papered with white Hanji (traditional paper), and the windows are covered with a thin layer of Hanji that lets sunlight or moonlight in between the muntins, revealing a silhouette of the outside vista. That’s what the ancients described as “borrowed scenery.”

Traditional Hanok are kept toasty through a floor heating system known as ondol. In this system, hot air from a wood fire is circulated through a system of flues that heat the floor stones (gudeul), which then radiate heat into the rooms. This radiant heating system has been modernized to use hot water, showing how Hanok incorporate not only the wisdom of the ages, but also the latest technology.

© Lee Kwan Jick.

© Lee Kwan Jick.

Korea has undergone rapid urbanization over the past century, and many homes were built with modern layouts and in Western architectural styles. At the same time, Koreans naturally sought to update Hanok style while preserving traditional methods. Hanok were built along steep, narrow alleys, answering the demands and social conditions of the time. Hanok of this sort can still be seen in Bukchon, Seochon, Ikseon-dong and Bomun-dong in Seoul.

A Hanok accommodation located in Hadong-gun County, Gyeongsangnam-do Province. © Hadong-gun County.

A Hanok accommodation located in Hadong-gun County, Gyeongsangnam-do Province. © Hadong-gun County.

Over the past two decades, Koreans have gained a fresh appreciation for Hanok’s appeal, which is so different from contemporary architecture, leading many to be repurposed as cafés, shops and workshops. Outside of Seoul, Hanok neighborhoods in such cities as Jeonju, Gyeongju, Naju and Gunsan have become tourist draws. Those tired of apartment life rediscovered the advantages of Hanok, leading to a boom in Hanok construction. Hanok clusters of various sizes and purposes have popped up around the country, such as Seoul’s Eunpyeong Hanok Village.

Hanok include their technical elegance, their multifaceted sense of space and the harmony of their visual beauty. The style is a masterclass in the concepts of condensing and unfurling. A Hanok changes with the terrain, guiding our eyes diagonally such that the smallest movements cause spaces to seemingly overlap or expand. The roofline has a curious vertical symmetry, with the furrows between the tiles seeming to mirror the rafters under the eaves. The top-heavy roof on a handful of wooden posts angles up like spreading wings, creating a lithe and airy effect despite its immense weight.

Hanok are environmentally friendly, being carbon neutral. The components of a Hanok are assembled through interlocking joints, with no need for nails or pegs. That is one of the biggest advantages of a Hanok, making it easier to replace damaged pieces or even disassemble or revise the entire structure.

Furthermore, Hanok are a good match for Korea’s traditional clothing and cuisine, which have been gaining popularity recently. Hanok are emerging as new cultural spaces that are bringing Korea’s unique and unforgettable beauty and charm to people around the world.

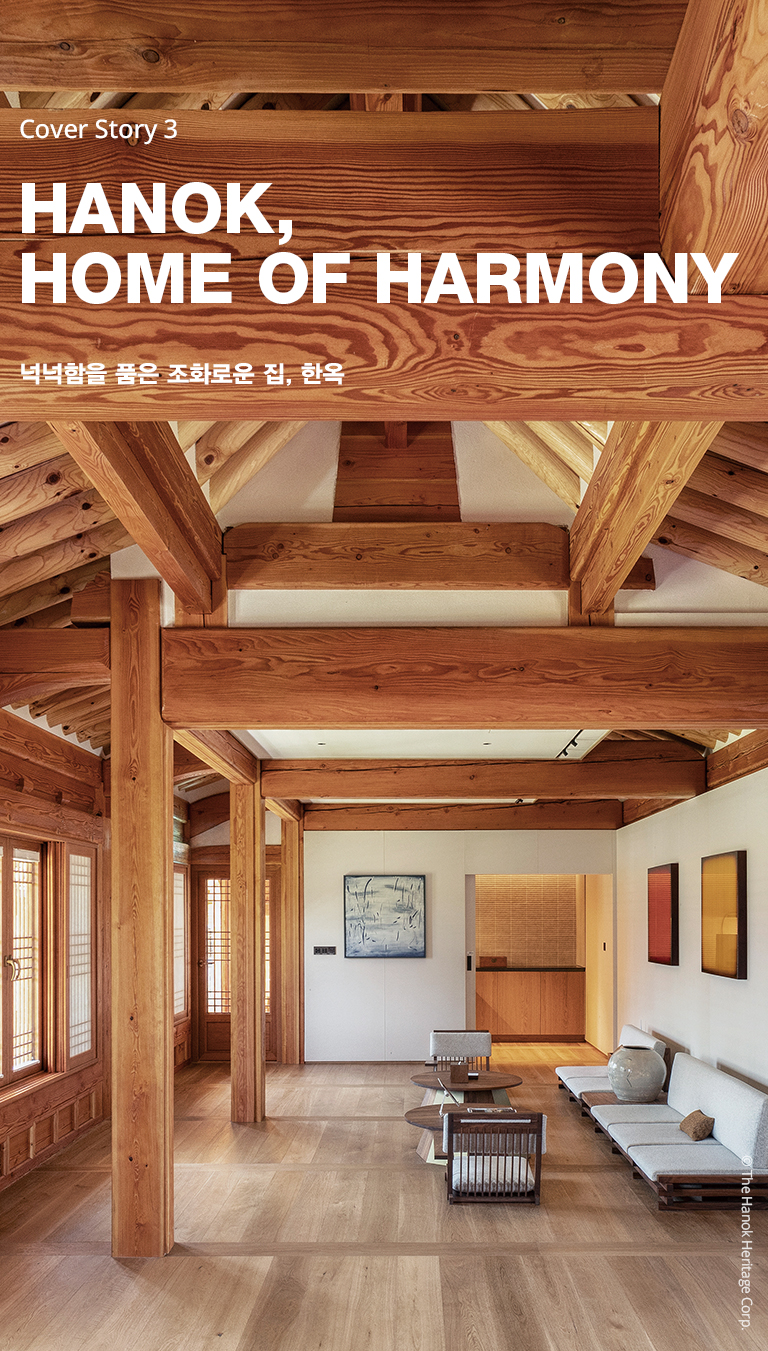

“The Hanok Heritage House,” a Hanok-style hotel located in Yeongwol-gun County, Gangwon State (Gangwon-do Province), combines the traditional beauty of Hanok with the simplicity and convenience of modern architecture. The hotel became the first building designed by a Korean architect to receive the Prix Versailles 2024, a series of architectural competitions that shine a light on the finest contemporary projects worldwide, organized by UNESCO and the International Union of Architects. © The Hanok Heritage Corp.

“The Hanok Heritage House,” a Hanok-style hotel located in Yeongwol-gun County, Gangwon State (Gangwon-do Province), combines the traditional beauty of Hanok with the simplicity and convenience of modern architecture. The hotel became the first building designed by a Korean architect to receive the Prix Versailles 2024, a series of architectural competitions that shine a light on the finest contemporary projects worldwide, organized by UNESCO and the International Union of Architects. © The Hanok Heritage Corp.

Writer. Lee Kwan Jick

Lee Kwan Jick, a public architect for the city of Seoul, is the CEO of BSD Architects and an adjunct professor at Korea University.