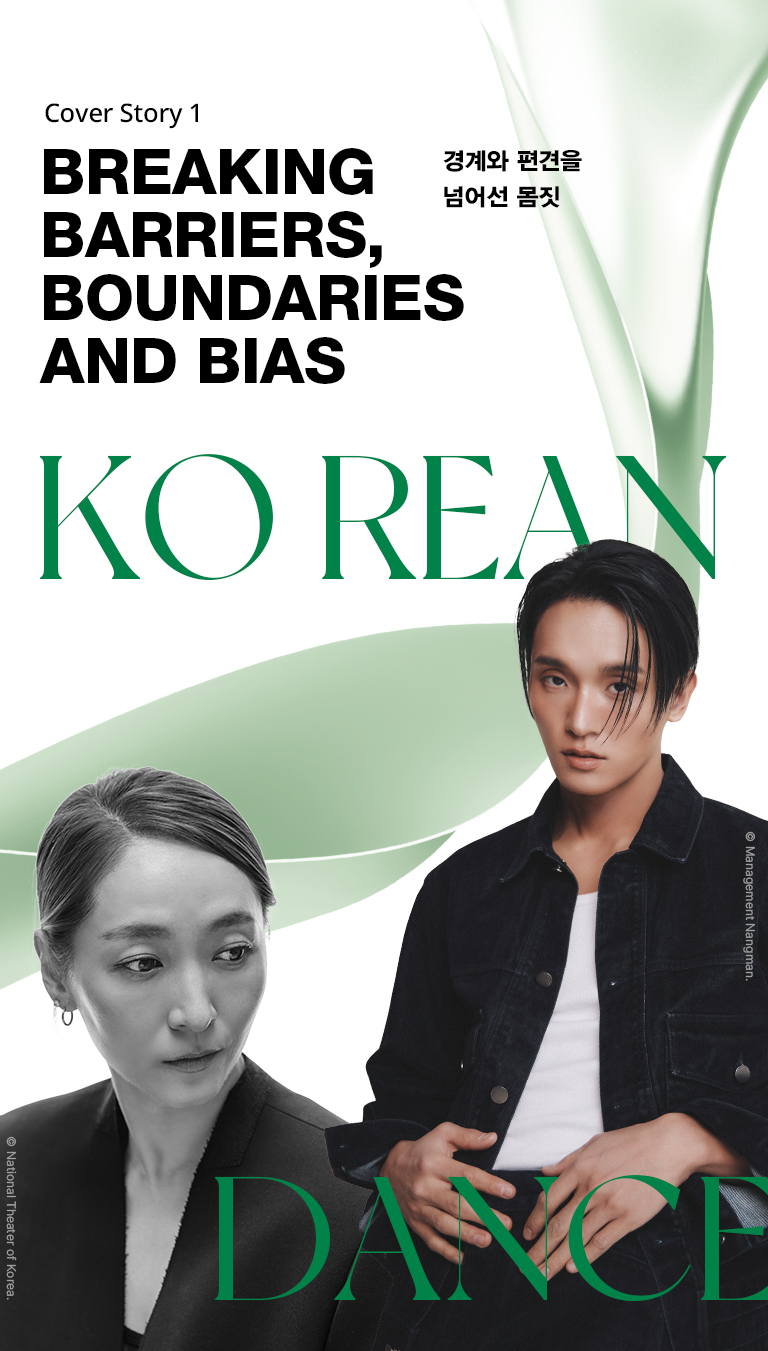

The once-serene image of Korean dance has recently undergone a transformation. What was once remembered for its quiet, slow movements is now being recognized as an art form that is fast, dynamic and even experimental. We met with dancers who have led this change, breaking stereotypes with their revolutionary movements.

최근 한국무용의 이미지가 바뀌었다. 고요하고 느릿한 움직임으로 기억되던 한국무용은, 빠르고, 역동적이며, 실험적인 감각마저 품은 예술로 새롭게 인식되고 있다. 이런 변화를 이끈, 고정관념을 깬 몸짓을 구사한 무용수들을 만났다.

Writer. Sung Ji Yeon

Dance has been Jung Bo-kyung’s entire life. She began dancing at age seven and majored in Korean dance through high school and university. In 2007, she gained critical attention, and in 2010, she became the first Asian to win the Grand Prix at the Bilbao ACT Festival. In 2020, she was the first Korean dance artist selected as an ARKO partner, leading to the establishment of her dance production company. She has presented numerous acclaimed works including “Gaksi,” “One,” “Thank You,” “Things to Come,” “Hello, My Grme,” “Beauty,” and Stage Fighter’s “Squid Game.”

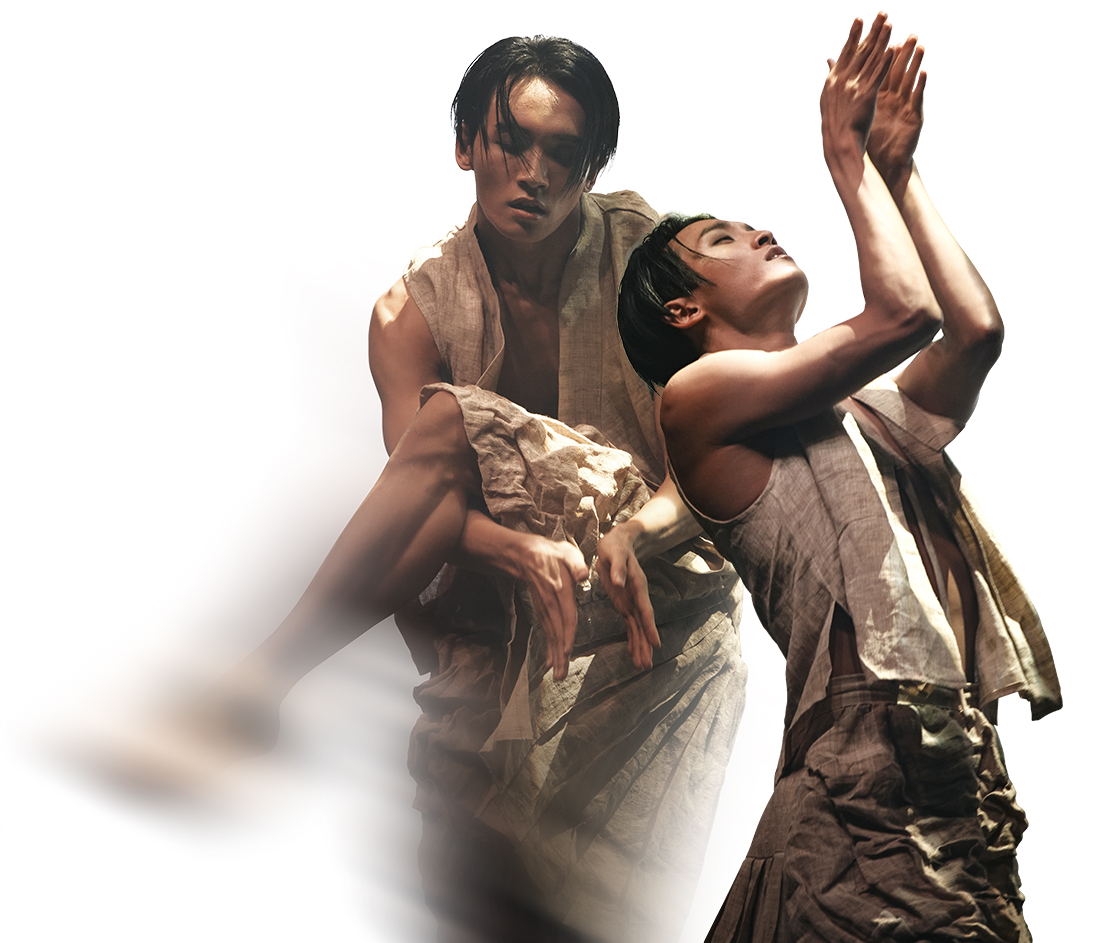

‘Beauty’ by the National Dance Company of Korea, choreographed by Jung Bo-kyung

‘Beauty’ by the National Dance Company of Korea, choreographed by Jung Bo-kyung

© National Theater of Korea, courtesy of Jung Bo-kyung.

Jung Bo-kyung, Korea’s most promising choreographer, stands out in her field with a unique genre of dance. Jung’s works can be considered a genre of Korean dance in herself. While rooted in Korean dance, she believes that “dance is ultimately one.” She defines dance as “the purest story conveyed through the body.” To create such dance, she decided to preserve the roots of Korean dance while refusing to distinguish boundaries between genres. Through this approach, she has achieved both universality and uniqueness.

This is no easy task. Unlike modern dance with its linear and rapid movements, Korean dance features predominantly curved, connected and slower movements. Jung Bo-kyung possesses the ability to harmonize these two styles. To achieve this, she penetrated to the core of Korean dance, focusing on what Korean dance seeks to convey through gesture and where its curved movements originate. Korean dance conveys context and emotion, manifests through rhythm and breathing, and reveals itself as explosive energy within restrained movement. She kept in mind that the predominance of curved movements derives from nature.

Concentrating on these elements, she preserved Korean dance’s locality by maintaining the “materials of dance” as raw materials for expression and “circularity and low center of gravity” as core aspects of expression. Simultaneously, she continuously varied group choreography and added free, rhythmic contemporary elements.

Everything in Jung Bo-kyung’s works goes beyond simply mixing Korean dance with other elements. The seams between genres are so smooth they become indistinguishable. Particularly, music and movement align so exquisitely that viewers feel as if they are “seeing” the music. The pacing throughout her works is also perfect. As a result, the movements and mise-en-scène she conceives become the most precise means of expressing her themes. Those who witness her performances feel thrilled and intuitively grasp her message.

While Jung Bo-kyung is recognized for opening the path of contemporary Korean dance, she doesn’t rest on these laurels but continues moving forward. “I hope that someday people will remember me as an artist who never stops striving.” We can expect that the new facets of Korean dance she will reveal through her works—approaching everything with whole-hearted dedication—will exceed our imagination.

‘Squid Game’ in Mnet’s ‘Stage Fighter,’ choreographed by Jung Bo-Kyung

‘Squid Game’ in Mnet’s ‘Stage Fighter,’ choreographed by Jung Bo-Kyung

Courtesy of Jung Bo-kyung.

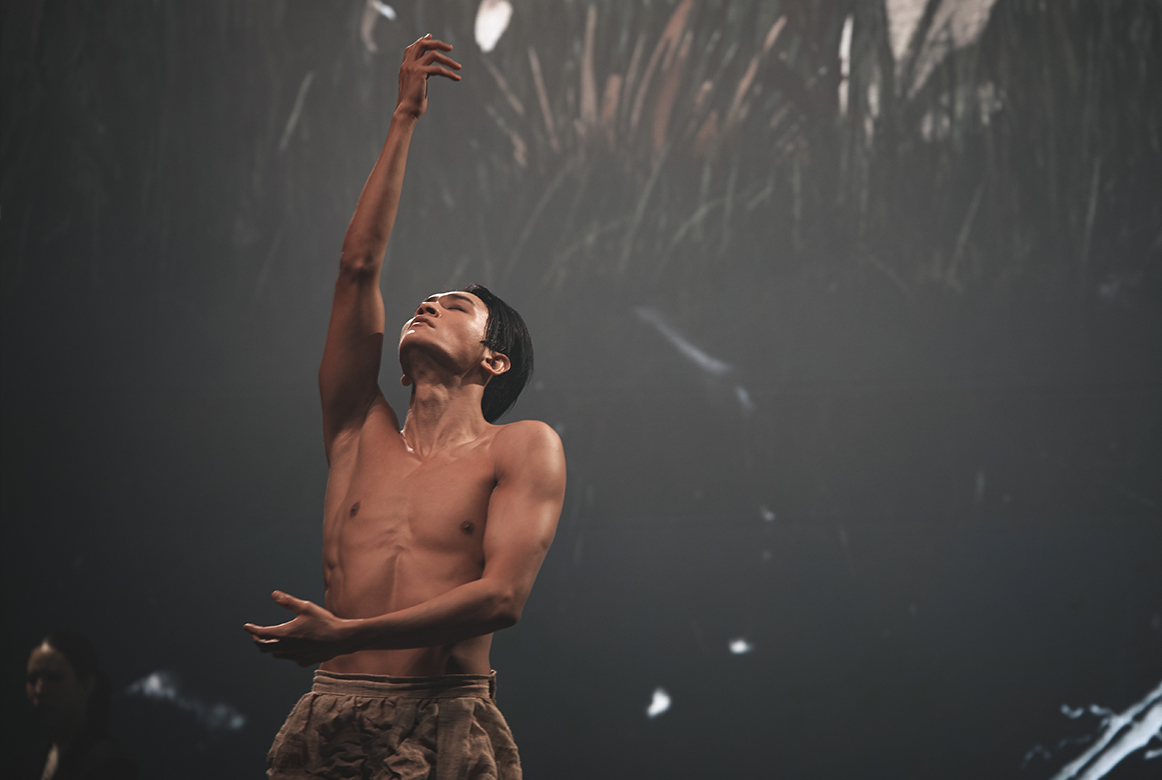

Choi Ho Jong is the winner of Stage Fighter, acclaimed for his reinterpretation of traditional dance. With achievements including the Dong-A Dance Competition award, joining the National Dance Company as its youngest member and holding Korea’s first solo Korean dance concert, he has introduced the charm of Korean dance to a wide audience. We interviewed him about his inspiring journey.

Q. You started at 19, which seems relatively late compared to others. How did you try to overcome the lost time? I worked that much harder because of it. I had feelings of inferiority, but at some point I realized I needed to dance for my own happiness, not for competition or others. I still maintain that attitude today.

Q. What helped you overcome feelings of inferiority? I once danced spontaneously for five or six hours straight. I danced intensely, then gently, my skin getting soaked with sweat and then drying, over and over. Through this process, I broke free from my inferiority complex. I reflected on the reasons for dancing and performing on stage, found my own answers and gained enlightenment. After that, my perception of dance and my personal skills noticeably improved.

Q. What events since then have shaped who you are today?

In my youth at the National Dance Company, I often felt lonely while trying to prove myself and gain recognition from others. After the company schedule ended at 5 p.m., I would go to other practice rooms and move my body until late at night. I got injured a lot, but I tried not to let those moments slip away.

Participating in “Stage Fighter” was also one of life’s important events. It was intense, but I discovered that I could enjoy that intensity. I always felt excited. I participated thinking I could set a good example as an artist, and I worked hard toward that goal. However, I believe I was only able to maintain my attitude as an artist.

Q. What is your artistic attitude? Approaching the stage with authenticity and not losing my center. In other words, no matter what situation arises, not losing my artistic vision or identity. I may not be confident in my skills yet, but I believe my passion for the stage is second to none.

Q. Where do you think your passion for the stage comes from? A desire to avoid stagnation, to constantly break free and move forward. I’ve come this far through the shock of seeing art that I thought was right yesterday show a different face today.

Q. During your TV appearance, both participants and viewers praised your choreographic skills and ideas. What’s your source of inspiration? I draw from many things—literature, animation, movies and more. I organize all my thoughts in a note application, writing down diary entries and fleeting ideas for the past 10 years. Even after writing them down, I continue to refine them.

Q. Since the end of “stage fighter,” korean dance has gained more attention. What do you think is its appeal? I think it’s the unique emotion of Korean dance. The spirit that Koreans are born with is fully embodied in the dance movements and expressions. The breathing and curves that express this create Korean dance’s distinctive beauty.

Q. What needs to happen for korean dance to develop further? While preserving the form itself is important, I think we need an approach that deconstructs it and interprets the emotions contained within from the perspective of contemporary Koreans. Genres develop by breaking down and rebuilding boundaries. So for a genre to develop, there must be people who preserve its characteristics, people who develop tradition and people who destroy tradition.

Q. What kind of dancer do you want to become? I want to be someone who doesn’t waver. I honestly didn’t know a day like this would come. I dreamed of such days, but at some point I started looking toward what comes next—my happiness. Like then, I don’t want to be overwhelmed by the present or lose sight of what matters. So showing good stages and good dances is natural. I’ll continue to work hard. Furthermore, I want to enhance my expertise and become a person with good character.

Q. Do you have any future plans? I want to expand my scope as a director and choreographer. I’m serving as associate artistic director of SAL (Subverted Anatomical Landscape), a dance company that presents experimental works without limiting itself to genres within dance. In July, I plan to present a work called “Virgin Soil” through SAL’s “GAMMA.”

© Management Nangman.

© Management Nangman.