Gochujang is unique among chili pastes for its flavor and texture. But this paste is unlike other Korean traditional ingredients in that its origins are relatively recent. Its story speaks volumes about Korea’s changing relationship with overseas nations—and how Korean cuisine adapted to the modern world.

Writer. Tim Alper

Korean cuisine’s backstory is, broadly speaking, a tale of evolution, rather than revolution. Preparations like kimchi, doenjang (soybean paste) and tofu and namul (seasoned herbs) have a history stretching back thousands of years.

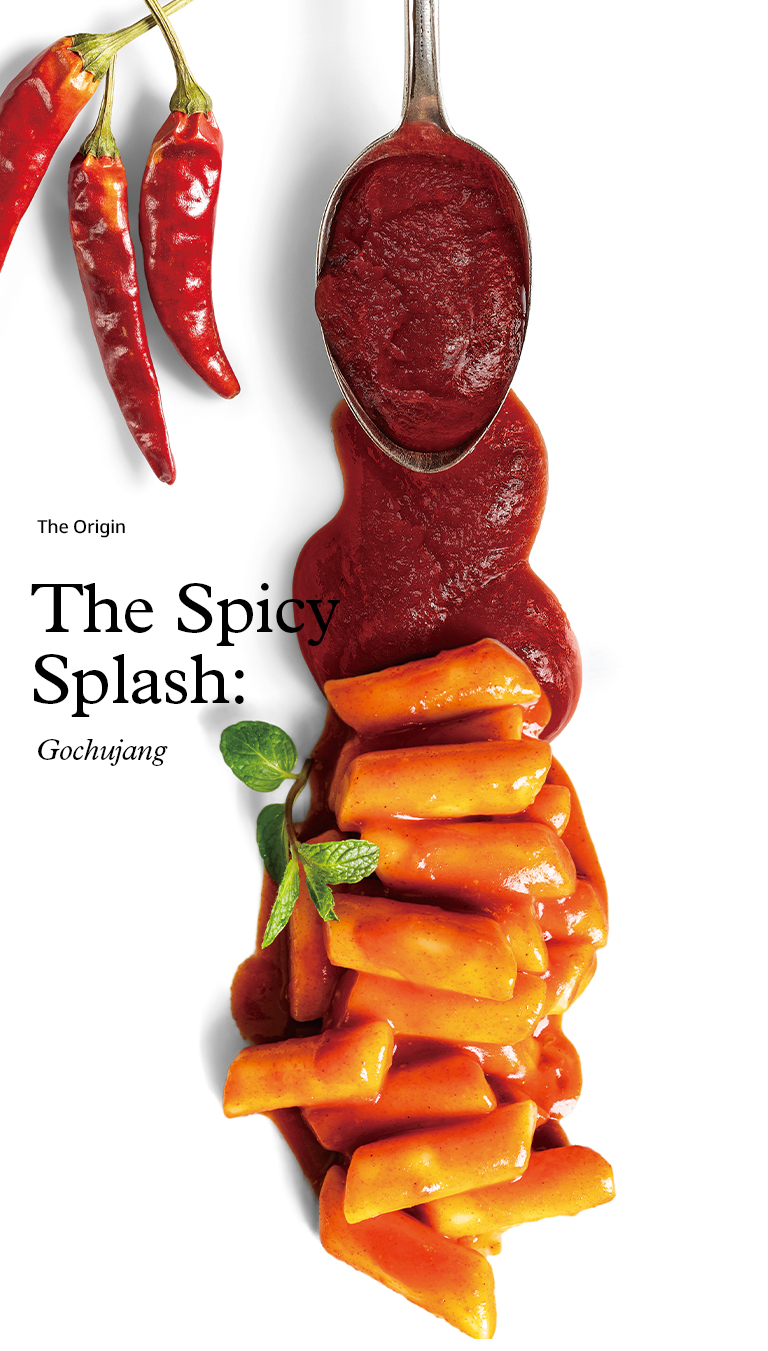

But the famous spiciness of Korean food is a relatively recent development. The chili peppers only arrived on the Korean peninsula in the 16th century. But it changed Korean food very rapidly and significantly. And by giving birth to gochujang (red chili paste), it is now doing the same in kitchens the world over.

© Getty Images Korea.

© Getty Images Korea.

Chili pastes are very common in global cuisine. You can find them all over the culinary world. Mexico is famed for its chipotle paste. Thailand’s nam prik pao (red chili paste) has become an international pantry staple. Cili boh is a cornerstone of Malay and Singaporean cuisine. You can also find a range of mouthwatering chili sauces in many African and South European nations.

But gochujang differs from all of the above because, despite its somewhat misleading English translation (“Korean chili paste”), there is more to this beguiling ingredient than meets the eye. Chipotle paste, cili boh and the rest are all unique in their own way. But in every case, their chief (and sometimes only) ingredient is chili pepper.

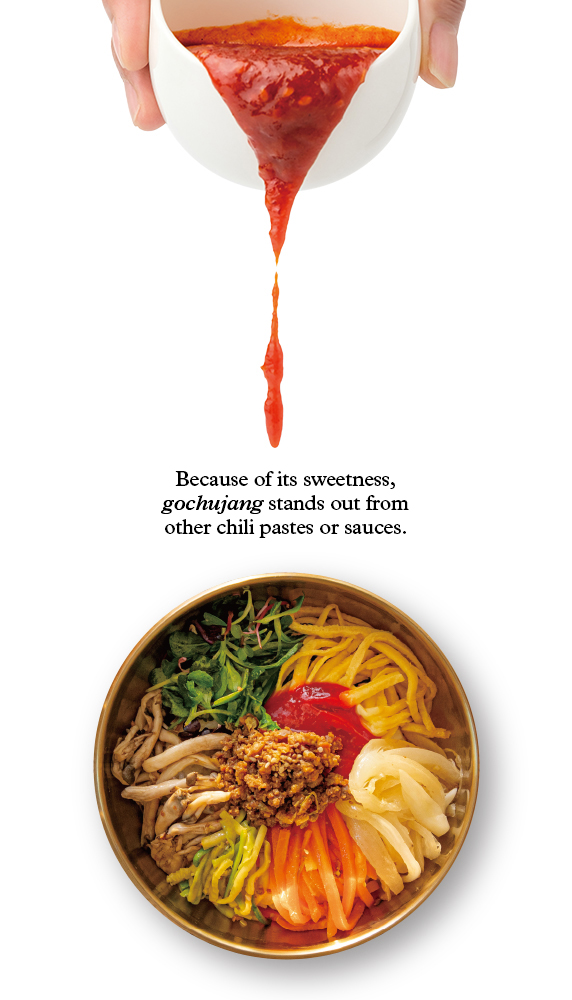

Gochujang, meanwhile, is yet another in a long line of Korean pantry essentials that make use of dried, fermented soybeans. While gochujang contains chili peppers, they are not its only ingredient by a long shot. In fact, to make gochujang, you need to add an equal amount of meju powder (dried, ground soybeans), as well as smaller amounts of glutinous rice powder, salt and other ingredients like malt and sometimes sugar or jujubes. Because of this, gochujang stands out from other chili pastes or sauces from around the world by offering a distinctive combination of spiciness and sweetness.

(Top) © Shutterstock / (Bottom) © TongRo Images Inc.

(Top) © Shutterstock / (Bottom) © TongRo Images Inc.

There is some evidence that Koreans made a preparation called “gochujang” prior to the 16th century. But it is highly likely that this bore very little resemblance to the product that began to spread across the country in the 1500s after Portuguese traders first brought the chili pepper to East Asian shores.

By the 1600s, Korean written records show, people all over the peninsula were growing peppers and incorporating them into their cooking. Books on agriculture and food preparation from the 1700s provide readers with detailed explanations on how to make gochujang—with recipes essentially identical to those used by modern Korean cooks.

Like many other Korean ingredients, the fermentation process gives gochujang an incredibly long shelf life. This granted it instant popularity. It also brought a brand new dimension to Korean food: spiciness—and a spiciness that could be enjoyed long after the pepper harvest was done.

(Left) Yangnyeom chicken: fried chicken tossed in a sweet gochujang-based sauce © TongRo Images Inc.

(Left) Yangnyeom chicken: fried chicken tossed in a sweet gochujang-based sauce © TongRo Images Inc.

(Right) Tteokbokki: rice cakes, sausages and fish cakes simmered in a gochujang-based sauce. This photo shows a creamy variation made with heavy cream or milk added to the gochujang base. © TongRo Images Inc.

Storing gochujang is relatively straightforward in the modern world. Most store-bought, commercially made gochujang—the kind now found in supermarkets everywhere—is shelf-stable, although most manufacturers recommend refrigerating their products once opened. In the fridge, gochujang can last for quite a long time.

But in the past, cooks had to use more inventive ways to keep their gochujang from spoiling. They used onggi, distinctive earthenware pots often kept outside, to store their precious paste. The same pots are also used to ferment and store all sorts of other Korean preparations, from kimchi to rice-derived alcoholic beverages.

Onggi predates gochujang by hundreds—even thousands—of years. Fired to temperatures of up to 700°C, these semi-porous vessels help ripen and preserve their contents, while also protecting them from potentially harmful bacteria, sunlight and heat. Some of the earliest pioneers of gochujang discovered that filling their pots with hot wood coals not only helped kill harmful microorganisms, but also gave their chili-based pastes a slightly smoky aroma and taste.

© TongRo Images Inc.

© TongRo Images Inc. © CJ Cheiljedang.

© CJ Cheiljedang.

For making gochujang, traditionally, Korean cooks would begin the process by preparing blocks of meju. While these are not impossible to make in a modern kitchen, they involve months of planning, as beans must be air-dried into rock-hard blocks for weeks before they are eventually ground into powder.

Instead, many cooks based outside Korea—and the vast majority of Koreans—now use store-bought, factory-made gochujang. These are usually sold in distinctive, rectangular plastic red tubs, making them easy for Koreans and non-Koreans alike to find on supermarket shelves. Of course, it is possible to make it yourself. These days, many of the ingredients used in gochujang, dried and finely ground, are also available at markets.

In Korea, gochujang is used in a range of famous and popular preparations, including bibimbap—a bowl of rice topped with vegetables and sesame oil. Diners are usually provided with gochujang to add and mix into their food at the table.

Searching for gochujang on social media platforms like Instagram reveals countless recipes shared by people worldwide using this Korean red chili paste.

Searching for gochujang on social media platforms like Instagram reveals countless recipes shared by people worldwide using this Korean red chili paste.

Outside Korea, cooks everywhere from Paris to Pennsylvania and Peru are starting to use the paste to prepare non-Korean dishes like spicy pasta. Some vegan cooks also use it to season air-fried tofu. Others use it to liven up vegetables, such as cauliflower, broccoli and oven-roasted carrots. A few mavericks even use it in desserts, adding spoonfuls to cookies, cheesecakes and brownie recipes.

Gochujang’s lasting and increasingly wide-ranging appeal is a testament to its uniqueness. By blending ancient cooking methods and onggi technology with a new world ingredient, Koreans have created something that is at once quintessentially Korean and beguilingly exotic. And that—perhaps—is what is now helping spread its popularity all across the globe.

500 g chicken thigh meat, 1 sweet potato, 1/2 onion, 1/8 cabbage, 1/2 green onion, 2 cups mozzarella cheese, 1/2 cup milk, 2 Tbsp gochujang (red chili paste), 2 Tbsp red pepper powder, 2 Tbsp cooking rice wine, 2 Tbsp ganjang (soy sauce), 2 Tbsp sugar, 2 Tbsp minced garlic, 1/3 Tbsp minced ginger, a pinch of curry powder, a pinch of black pepper, 1 Tbsp sesame oil