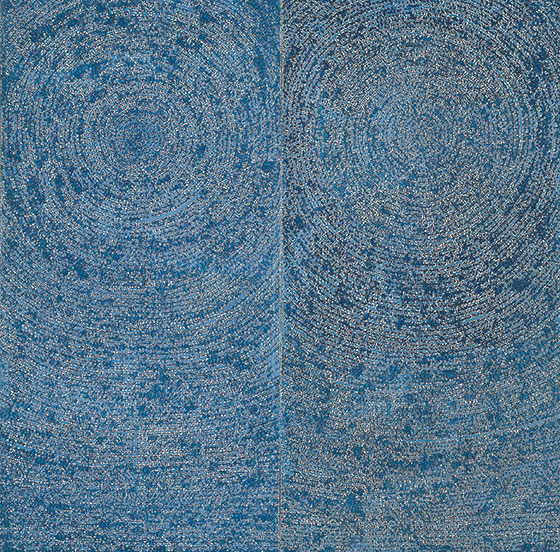

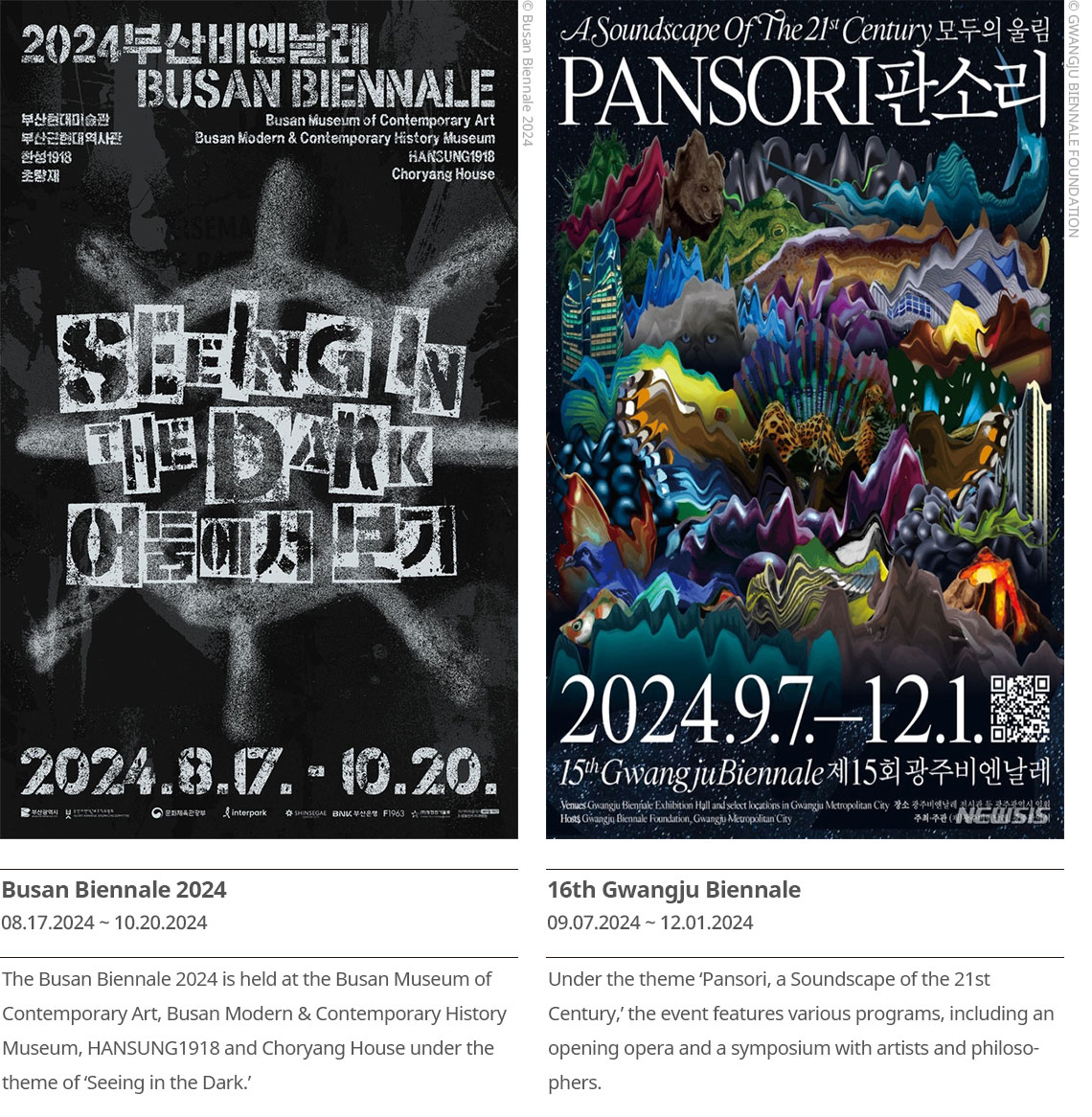

The world is taking notice of the most incredible art from one of the hottest cultural hotspots: Korea. With its modern reinterpretation of tradition and labor-intensive craftsmanship that borders on the sublime in its delicate aesthetics, Korean art is riding the global Korean cultural wave to even greater heights. There’s a growing interest in fresh, innovative artists. Showcasing this trend, Korea’s premier art fair, “Kiaf SEOUL,” the international “Frieze Seoul,” and the Gwangju and Busan Biennales will simultaneously open in September. Come and explore the captivating charm of Korean art, a nationwide celebration that is heating up the entire country into a veritable “Korean Art Festival.”

Writer. Cho Sang-in

The Dawn of Modern Art Rooted in Tradition

Ancient Korean art was deeply intertwined with religion and the political elite, from Goguryeo tomb murals to Baekje Buddha statues and Silla gold crowns. This parallels Western art history, where the “liberation of art” is a modern phenomenon. During the Joseon Dynasty, professional painters worked under the Royal Academy of Painting (Dohwaseo) with masters like Kim Hong-do and Shin Yun-bok. The 1894 Gabo Reform abolished the Dohwaseo, leaving court painters unemployed. They began sharing court styles with the public, coinciding with the rise of a new wealthy merchant class eager for art.

This period also saw Joseon dynasty opening to foreign influences, allowing “new art” to permeate the country. Kim Young-na, an art historian, former director of the National Museum of Korea, and now an emeritus professor at Seoul National University, provides valuable insights into this era. Her book, “Korean Art: From the Opening of Ports to Liberation,” notes that the 1880s marked a pivotal shift. Traditional categories like seohwa (painting and calligraphy), sang (sculpture) and doja (ceramics) began to be collectively termed “art” for the first time. Kim views “the 1880s, when new changes first appeared, as the starting point of modern art.”

Go Hui-dong, tutored by the last Dohwaseo painter, Cho Seok-jin, became Korea’s first formal Western painting student at the Tokyo Academy of Fine Arts in 1909. In 1921, Na Hye-seok, educated at Joshibi University of Art and Design, held Seoul’s first Western-style solo exhibition. As a new woman, she embodied the spirit of modern artistry in Korea.

Rha Hyeseok, Self-portrait,

Rha Hyeseok, Self-portrait, 1928, oil on canvas, 89x76 cm

© Suwon Museum of Art

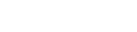

Park Soo-keun, Tree and Two Women,

Park Soo-keun, Tree and Two Women, 1962, oil on canvas, 130x89 cm

© Leeum Museum of Art

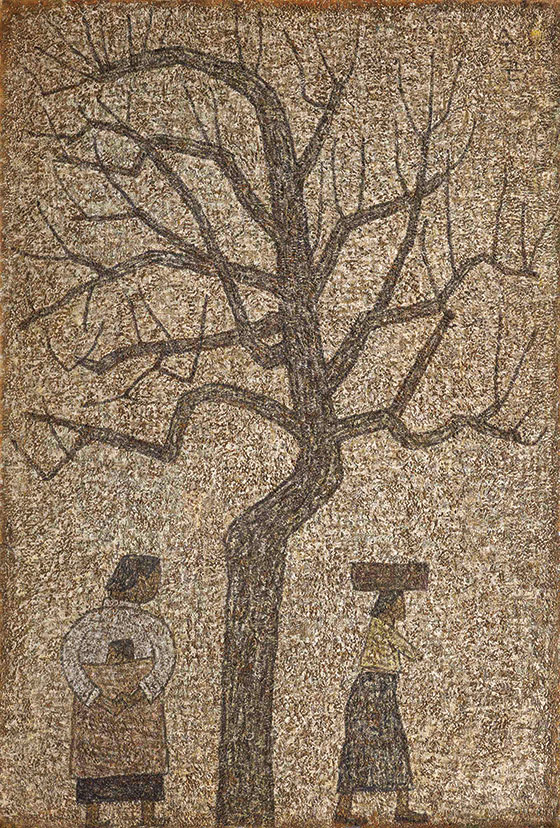

Kim Whanki, Universe 5-IV-71 #200,

Kim Whanki, Universe 5-IV-71 #200, 1971, oil on cotton, 254x254 cm

© Whanki Foundation·Whanki Museum

Modernization of Tradition: Korean Art’s Subversive Experimentalism

The allure of Korean art lies in its modernity and innovative challenges, built upon a foundation of history and tradition. Lee Ungno (1904-1989) progressed from ink paintings of bamboo to Japanese art techniques before moving to France in 1959 to explore experimental art. He ultimately developed his unique abstract style. Park Soo-keun (1914-1965), a beloved national painter, drew inspiration from Gyeongju’s rock-carved Buddha statues. He created a distinctive style by repeatedly layering unmixed oil paint, producing images resembling stone carvings. Lee Jung-seob (1916-1956), a tragic genius, infused his cow paintings with the national spirit. Influenced by Goguryeo tomb murals he saw as a child in Pyongyang, he combined Goryeo celadon inlaying and metal craft techniques to create “silver foil paintings”—the first Korean works acquired by New York’s the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Kim Whanki (1913-1974), a pioneer of Korean abstract art, admired moon jars for embodying Korean aesthetics. His works, featuring white porcelain motifs, culminated in all-over dot paintings inspired by ink’s spreading effect.

Yun Hyong-keun (1928-2007), Kim’s student and son-in-law, continued exploring ink’s depth. Influenced by Chusa’s calligraphy and Eastern philosophy, he aimed to capture nature’s principles in his paintings, attracting international collectors with his distinctly Eastern approach. Korean abstract art in the 1970s diverged from Western monochrome and minimalism. Dansaekhwa (monochrome painting), exemplified by Kim Whanki and Yun Hyong-keun, gained global recognition by infusing traditional exploration with natural reverence, quiet spirituality and relentless performativity. Park Seo-bo’s “Ecriture” technique, rooted in Hanji (traditional Korean paper), evolved into “color ecriture” post-2000, offering healing through natural hues. Chung Sang-hwa’s ceramic-inspired paintings and Ha Chong-hyun’s innovative “back pressure method” have further piqued international interest in Korean contemporary art.

Lee Ufan, Korea’s most renowned living artist, synthesizes technique and philosophy, embodying tradition, modernity, nature and East-West philosophical fusion. This synthesis is why he has become so famous.

Korean art’s strength also lies in its subversive “Dynamic Korea” aesthetics. Nam June Paik, a Korean-born global icon, pioneered “video art.” The experimental artists of the 1960s-70s, showcased at New York’s Guggenheim in 2023, are being reevaluated for their avant-garde approaches.

Korean art’s intensity stems from exploring historical consciousness and social issues. The North-South division is a uniquely authentic subject for Korean artists. Artists addressing themes like the Korean War, democratization, and rapid industrialization have been featured in international exhibitions. Lee Bul (focused on women’s and human rights), Choi Jeong Hwa (who critiques industrialization through kitsch), Suh Do Ho (who explores identity), Kim Sooja and Yang Hae-gue have collectively elevated Korean art’s global status.

Kimsooja, To Breathe : Bottari, 2013,

Kimsooja, To Breathe : Bottari, 2013, The 55th Venice Biennale, courtesy of Kukje Gallery & Kimsooja Studio, photo by Jaeho Chong

© Kukje Gallery

Park Seo-Bo’s ‘Ecriture’ works in collaboration with Louis Vuitton’s ArtyCapucines

Park Seo-Bo’s ‘Ecriture’ works in collaboration with Louis Vuitton’s ArtyCapucines© PARKSEOBO FOUNDATION

Dynamic Korea, Diverse K-art

The future of Korean art is propelled by its diversity, as exemplified at the 60th Venice Biennale. Abstract art pioneers Yoo Youngkuk and Rhee Seundja are drawing crowds with their special exhibitions. Visitors flock to see Shin Sung Hy’s spatial creations of cut and woven canvases and Lee Bae’s charcoal works depicting nature’s cycles. The Biennale’s leading exhibition showcases a spectrum of Korean artists, from modern painters Lee Quede and Jang Woo-sung to Kim Yun Shin, who hand-carves wood and stone to express the essence of artistic humanity. Lee Kang Seung’s work stands out, using beautiful sign language and intricate embroidery to tell the stories of historically marginalized sexual minorities.

International art professionals visiting Korea invariably inquire about “new artists.” Frieze Seoul has expanded its nighttime events, adding “Euljiro Night” to the existing “Samcheong Night” and “Hannam Night.” This initiative aims to spotlight emerging talents in Euljiro’s new art spaces, shifting focus from established large galleries.

The global Hallyu (Korean Wave) has amplified interest in Korean culture, naturally extending to its art scene. This curiosity about the wave’s origins has led many to explore Korean art. K-art benefits from celebrity endorsements, with Korean Wave stars like BTS’s RM and BIGBANG’s GD and global luxury brand ambassadors promoting it on social media.

If Korean art were a car combining durability, design and eco-consciousness, it would have a well-paved highway to travel on. This infrastructure includes the Gwangju and Busan Biennales, which have nearly three decades of history, and the genre-diverse Seoul Mediacity Biennale of Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA), all serving as vital “art platforms.” Public museums and private institutions sponsored by corporations like Samsung and Amore Pacific further strengthen the art ecosystem. Robust government support ensures visitors can easily access art maps from Incheon Airport to Seoul City Hall. Shall we stop here and set out to experience an exhibition firsthand?

Writer. Cho Sang-in

Director of the Baeksang Art Policy Research Institute

Cho Sang-in has been covering the art scene for 17 years since 2008 at the Seoul Economic Daily. Cho Sang-in graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Archaeology and Art History from Seoul National University and a master’s degree in Arts Management from the same university’s graduate school. She wrote the popular book on Korean modern art, “The Surviving Paintings,” and serves on the Intangible Heritage Committee of the Korea Heritage Service, overseeing the traditional art and traditional crafts sections.