August 2021

August 2021

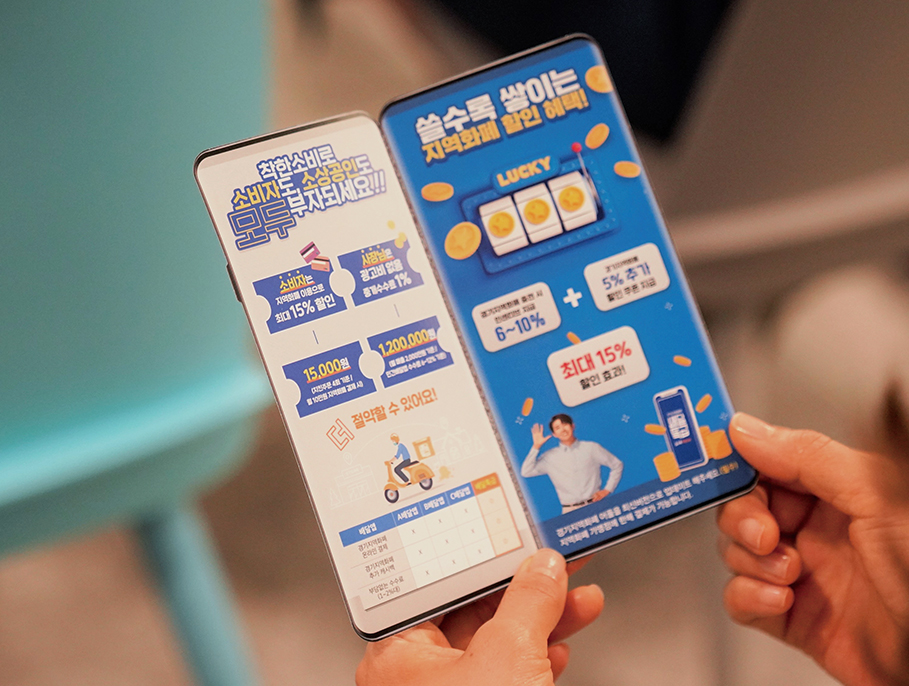

The food delivery market has experienced an unprecedented boom due to the protracted COVID-19 pandemic. The size of the domestic food delivery market was KRW 17.62 trillion (roughly USD 15.44 billion) as of 2020. Delivery apps account for more than half of the market’s transactions. Though the advent of mobile platforms has made it more convenient to use delivery services, there are also disadvantages, including the excessive fees that small business owners are charged. The Korea Gyeonggido Company created the delivery app Baedal Teukgeup (“Special Delivery” in Korean) to promote coexistence between delivery services, small businesses and customers.

Written by

Yu Pureum,

features editor

Photo courtesy of

Korea Gyeonggido

Company

In December 2019, a certain privately owned delivery app accounted for 99% of the local delivery market, sparking monopoly concerns. When the app eventually changed its fee system, small businesses found themselves burdened with excessive fees. They raised their prices in response, harming consumers.

Faced with this situation, local governments rushed to release publicly developed delivery apps. Gyeonggi-do Province was one such government. To sustainably run the service, the province needed an organization that could flexibly respond to the market while pursuing the public interest. They concluded that the Korea Gyeonggido Company, an entity created by the province, business organizations and other local groups to promote a “sharing market economy,” was the perfect candidate.

It wasn’t an easy mission. Internally, the company was on the verge of collapse due to repeated losses. Externally, the company had to deal with privately owned delivery apps armed with scale, technology and funds. The instability had an upside, though. Lee Seok-hun, the company’s CEO, said, “The unstable situation was rather an opportunity for internal solidarity.”

© clipartkorea

© clipartkorea

The publicly developed delivery app Baedal Teukgeup is contributing to coexistence among delivery industry stakeholders.

The publicly developed delivery app Baedal Teukgeup is contributing to coexistence among delivery industry stakeholders.

Despite doubts from experts, Baedal Teukgeup has achieved a market share of 10% in Gyeonggi-do Province. The service, which started in just three cities and counties, has expanded to 20. Users have generated KRW 35.6 billion (roughly USD 31.19 million) in transactions so far, while the number of subscribers has surpassed 390,000. Most encouraging of all, in a recent survey, the service was Korea’s top delivery app in terms of favorability. Lee attributed the result to the “many consumers and small business owners who empathized with the worthy purpose and various benefits of public delivery apps.”

Concerns about monopoly and oligopoly are rising in many different sectors. That’s why Lee has higher expectations for Baedal Teukgeup. He says, “If we demonstrate a successful model of public-private partnerships through Baedal Teukgeup, we can apply it to various fields in the future to solve the monopoly problem.” Lee hopes that Baedal Teukgeup will become the foundation upon which a mature delivery industry blooms.

CEO AND REALIZER

Lee Seok-hun

Q. What differentiates Baedal Teukgeup from private delivery apps?

Baedal Teukgeup provides services that are local and specialized. Private delivery apps view the whole country as a single area, while Baedal Teukgeup provides a service that brings out the local characteristics of a region by gathering the heads of local government offices and merchants. The goal is to help local consumers actually experience the benefits of the service. For example, in Yeoncheon, where there are many military facilities, soldiers account for 70% of local consumption. So we are considering ways to provide paper coupons soldiers can use through collaboration with military units.

Q. How do you strike a balance between coexistence and profits?

The most difficult part of this job is finding that balance. Our company conducts business with the public interest in mind, but if the business fails, we can’t help the public. Therefore, organization-wide empathy with the fundamental goal of the company is more important than the role of the chief executive. We constantly communicate with our employees about the purpose of our company and attempt to motivate them through job reassignments, reorganizations and other means.

Q. What is the goal of Baedal Teukgeup?

Our goal is to achieve self-reliance. At the beginning of the project, we had little choice but to use money from the provincial government. However, we are establishing a strategy that will allow us to run Baedal Teukgeup on our profits alone. When the service reaches its target market share of 15% and enters the stabilization stage, our next step will be to conduct e-commerce linked to local specialty products. We are also considering ways to create a new advertising market by adding a media commerce function.

In the 1960s, jajangmyeon (noodles in black bean sauce) began to dominate the food delivery industry. At a time when Koreans were struggling to achieve economic growth, many had their meals delivered to them from nearby markets as they barely had enough time to eat. Many call this the beginning of delivery food. By far, the most popular delivery food was―and still is―jajangmyeon, an easy-to-eat dish of noodles and black bean sauce. A great place to try this dish is the iconic restaurant Gonghwachun in Incheon’s Chinatown, which has been serving fine jajangmyeon since the early 20th century.

![]()

Written by

Hwang Jeong-eun,

Photographed by

Studio Kenn

Koreans have a sentimental attachment to jajangmyeon. The dish has long represented the common people. At one point, the price of jajangmyeon was even used to calculate the inflation rate. If the price of jajangmyeon showed signs of rising, the government would step in to block the increase.

Jajangmyeon is deeply rooted in the history of Incheon’s Chinatown, which grew with the opening of Incheon’s port in 1883. Indeed, the dish as we know it today was born in Chinatown, where immigrant Chinese chefs in the early 20th century adapted a popular Chinese noodle dish to local ingredients and tastes.

Incheon’s Chinatown flourished, but when measures to restrict foreigners from owning land were implemented in 1967, many Chinatown residents left the country for better economic opportunities abroad. In recent years, however, the community has begun to thrive once again, And as the city booms, so does jajangmyeon.

Jajangmyeon was born in Incheon’s Chinatown.

Jajangmyeon was born in Incheon’s Chinatown.

Once eaten only on special days, jajangmyeon is now one of Korea’s most commonly consumed dishes. © imagetoday

Once eaten only on special days, jajangmyeon is now one of Korea’s most commonly consumed dishes. © imagetoday

If there is one twist to jajangmyeon, it’s that it’s a Chinese dish found nowhere in China.

Study the history of the dish, and you’ll find that it’s based on a northern Chinese dish called zhajiangmian, prepared by mixing boiled noodles with vegetables and Chinese soybean paste. Simple and cheap, the dish proved popular with Chinese migrants who flocked to Chinatown after the opening of Incheon’s port. Zhajiangmian eventually morphed into today’s jajangmyeon, changing to suit Korean tastes.

Accordingly, jajangmyeon is a dish born in Korea, a piece of Korea’s historical and cultural heritage. Standing at the center of that heritage is the legendary Chinatown eatery Gonghwachun. Since its founding in 1912, Gonghwachun has been pioneering jajangmyeon, constantly evolving its recipes to keep up with changing tastes. Thanks to these efforts, diners can enjoy the iconic dish in new and more satisfying ways.

COOK AND CONTRIBUTOR

Lee Hyun-dae

Q. Once upon a time, Koreans could eat jajangmyeon only on special occasions. Now, however, it’s the country’s most popular delivery food. Why do you think jajangmyeon has become a favorite delivery food?

It’s probably due to its low price and convenience. It’s tasty, too. Delivered jajangmyeon has a drawback, though, in that it cannot properly preserve the grilled flavor. That grilled flavor is important to Chinese food, which is why it’s best to eat it immediately after it’s cooked. Nevertheless, jajangmyeon has been at the forefront of delivery food for a long time, perhaps thanks to the special sentiment attached to jajangmyeon in Korea.

Q. The original Ganghwachun closed in 1984, but you re-opened it in 2004.

When I first said I was re-opening Gonghwachun, everyone tried to stop me. At the time, Chinatown wasn’t so vibrant, so there was even more opposition. I think I’ve been able to come this far because of my sincerity and honesty. There are many difficulties when it comes to doing business, but I believe we should adhere to weighty principles, not thin tricks. Furthermore, I know that my current success is not due to my own efforts alone, so I am constantly donating to places in need.

Q. How you want people to remember jajangmyeon?

Chinese cuisine can be shared and enjoyed easily and conveniently by people of all ages and genders. My wish is that it will continue to be a food that people are familiar with. I also hope that people will start to reconsider the value of Chinese food. Ever since I re-established Gonghwachun in 2004, my goal has been to showcase high-end Chinese cuisine. I want to show that Chinese food is tasty and convenient, but also that you can enjoy it in more sumptuous ways, too. I hope people think of jajangmyeon as both a common and high-end dish.