Contents

Consilience

Hopping Ahead

In November 2012, an article in The Economist said that South Korean beer was bland and nowhere near as good as North Korea’s famed Taedonggang Lager. Almost six years on, what has changed?

Written by Daniel Tudor, former The Economist correspondent and current advisor to the foreign press team at the Presidential Office, Cheong Wa Dae

Photographed by Studio Kenn

Korea That Once Was a Beer Desert

At the time it felt like an afterthought, almost a flippant kind of piece. I’d been trying to write something about the 2012 presidential election, only to be rebuffed by an uninterested London-based boss. Usually he’d favor North Korea stories over South Korean ones, and quirky South Korean stories over proper news. That’s the curse of reporting on Korea for the international press: there’s always demand for something about plastic surgery or the “real meaning” behind Kim Jong Un’s waistline. As I sat in a bar drinking one of the two ubiquitous, identically bland lagers that pervaded the southern part of the peninsula, scratching my head about what to write, it hit me that the economics of beer ─ with a North Korean twist ─ seemed just about Economist-y enough as subject material.

It started with a series of inevitable questions. Why were there only two companies making all the beer in the whole country? How were their profit margins so high, and their investment in R&D so low? Why were their beers unidentifiable from each other in taste? Why, indeed, were they sold for the same price at every convenience store across the country? Clearly, you didn’t need to be Keynes or Friedman to identify the Korean beer market as a textbook duopoly.

It turned out that the law was helping them. Brewers were required to be able to store vast amounts of beer at any one time, more than 100,000 liters, if they wanted to sell beer anywhere other than on their own premises. You could run a brew pub, but that was it. In order to become a big beer company, you had to already be a big beer company. The two existing giants could trace their lineage back all the way back to the time of the Japanese colonial era. Nobody else could even get close to them.

Three glasses of freshly poured beer are ready to be served.

Three glasses of freshly poured beer are ready to be served.

Ka-boom

Or so it seemed. I heard about a man named Park Chul, owner of a brewing company named Ka-brew. According to another source, he was independently wealthy and had accumulated lots of brewing equipment, enough to get over the legal minimum requirement. He wasn’t necessarily using all that equipment at one time, but he did possess it, and that was the important thing.

Ka-brew arguably lay the groundwork for the craft beer boom by making beer for others on contract. For my article, I met Park along with Dan Vroon, the Canadian owner of Craftworks, one of Ka-brew’s customers. Craftworks, known for its range of beers named after Korean mountains like Baekdusan and Jirisan, was almost certainly the first North America-style craft beer bar in Korea.

In those days, craft beer in Korea was sold and drunk mostly by non-Koreans in places like the expat-heavy Gyungridan district of Seoul, and produced by Ka-brew. Mainstream Korea had never heard of IPA, pale ale or porter. People weren’t even aware of the legal restrictions that were keeping others from opening their own breweries.

A handful of malted barley becomes fresh beer. © Korea Craft Brewery

A handful of malted barley becomes fresh beer. © Korea Craft Brewery

That would all change when my article came out. I found it strange that week in, week out, I could write absolutely anything about politics or the North Korea issue to no reaction whatsoever, but with one mention of beer, I could become a semi-public figure. Particularly, the fact that I’d thrown in a comparison with North Korean beer seemed to ignite the controversy that would follow.

Local journalists bombarded me with phone calls and text messages, wanting to know if North Korean beer really was any good, and, if so, how I’d managed to get hold of some. To their surprise, I told them yes it was, or rather, at least it was better than South Korean lager, and that I’d actually tried it in South Korea. It isn’t well known, but North Korea’s Taedonggang Lager was imported into the South in small quantities during the Roh Moo-hyun administration, which had been continuing along the path of Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy of pursuing a closer economic relationship with the North.

It was then that I’d tried Taedonggang, at a chain pub named Wa Bar in downtown Seoul. It tasted like a typical European lager to me: not amazing, but certainly a step up from the main Korean brews, which, as most people would now agree, tasted of not very much in particular. Later, when I actually visited North Korea as part of research for a book, I came to try other North Korean beers. Taedonggang is just one of many. It amazed me that there was greater beer diversity in the North than in the South. My favorite was a brew named Gyeongheung, and honorable mentions also go to Bonghak and Ryongsong beers.

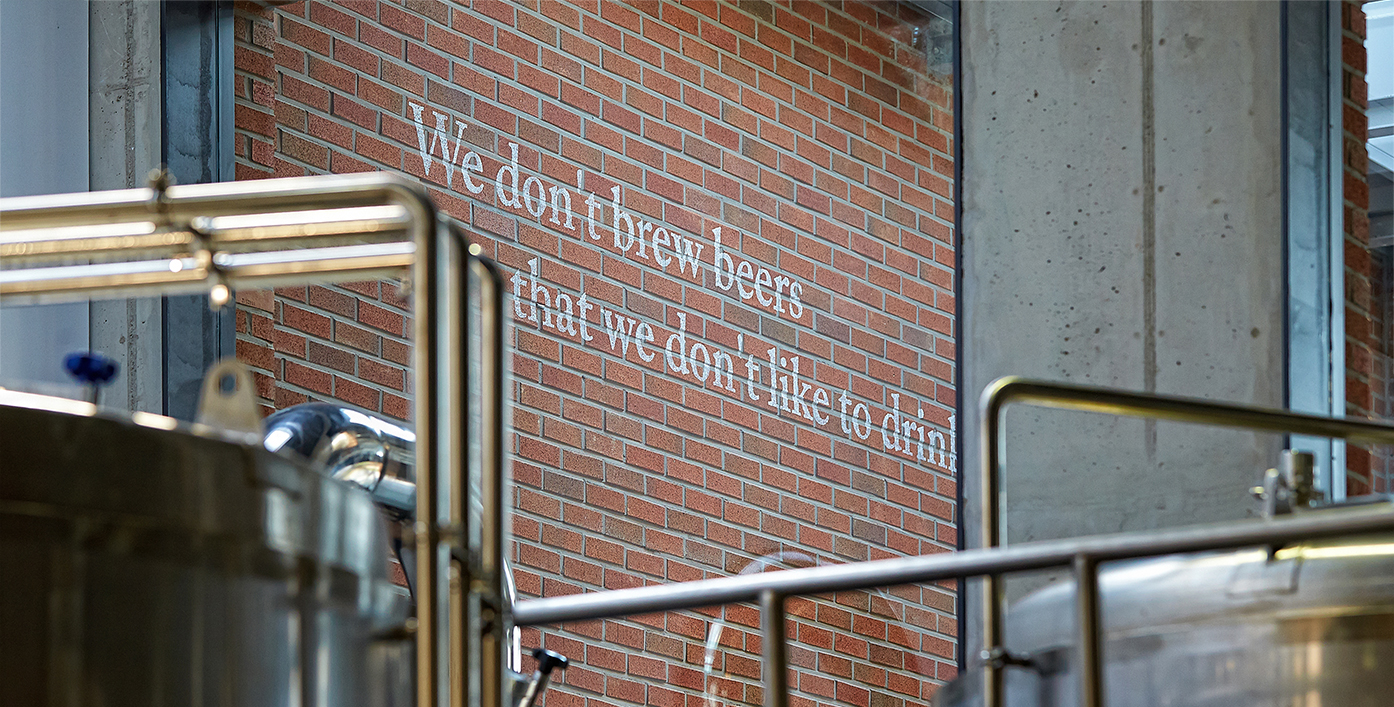

The philosophy of the brewery is written on the wall.

The philosophy of the brewery is written on the wall.

After the article came out, there was a period of surprise among columnists and talking heads across Korean media. Could it really be that North Korea was superior at making anything? Additionally, I feared a nationalistic reaction. In the past, when a non-Korean criticized anything in South Korea, there was always the possibility of an us-versus-them reflex response against not just the argument, but also against the person.

However, once a few weeks had passed, in which every major newspaper had editorialized on Korean beer, and the National Assembly had seen fit to debate it, as well, public opinion seemed to swing in my favor. Despite the two big beer companies’ best efforts, the controversy had been the red pill that took mainstream Korea out of the beer matrix.

Discussion then moved on to how to improve the situation. The core of the issue was a lack of diversity and competition, underpinned by the legal requirement that only Ka-brew had been able to get around. What was surely needed was a change in the law that would naturally result in the flourishing of small breweries up and down the country.

Endless rows of beer taps offer unique tasting experiences.

Endless rows of beer taps offer unique tasting experiences. The different ways people enjoy their beer is as diverse as the amount of beer tabs.

The different ways people enjoy their beer is as diverse as the amount of beer tabs.The Law Is No Longer a Barrier

Thanks to the efforts of beer fan and then-member of the National Assembly Hong Jong-hak, now minister for small business, the law on beer production was changed in 2014. Since then, something like 50 breweries have come into existence. Up and down the land, once-amateur brewers are clubbing together and buying land and equipment, and churning out all manner of different styles of beer.

The result of this is that the Korean beer landscape is now utterly unrecognizable from what it was just five years ago. Craft beer is still a very small segment of the market, 0.5 percent, to be precise, but this figure has been doubling every year. A typical projection for 10 years from now is for craft beer to account for one in 10 beers drunk in Korea.

Arguably the real beneficiary of the beer controversy, though, has been importers. Owing to the now widespread recognition of mainstream Korean beer’s failings, and surprisingly generous tax treatment for mass market non-Korean beers, around half of beer sold at Korean supermarkets now comes from abroad. The famous “four tall cans of imported beer for KRW 10,000” deal, about USD $10, is the way nearly everyone buys from convenience stores these days.

Going to the convenient store for beer is more popular today, as they offer more affordable deals for canned beer.

Going to the convenient store for beer is more popular today, as they offer more affordable deals for canned beer.

Though it was never my intention when I wrote the article, I have jumped into the industry myself. During the peak of the “North Korean beer is better than South Korean beer” controversy, a friend of a friend approached me. He explained that he and his wife-to-be were about to start a bar selling a craft beer made from a recipe provided by Bill Miller, a U.S. home-brewer famous among Seoul’s craft beer lovers. It would be made, of course, at Ka-brew. He asked if I wanted to join them. I said yes, and thus, The Booth Brewing Company was born.

We managed to ride the wave, and have managed to become one of the more well-known craft beer firms in Korea. Our flagship beer, Kukmin IPA, won a “best beer of the year” award in 2017 from one of the main Korean newspapers. There’s a lot of competition though these days. Perhaps three years ago, there were just a handful of craft beer companies, and anyone with a half-decent IPA could be up and in business. Now, you have to be really good.

For me, this is stressful, but for you, the reader, it can only be good news. So let me recommend a few places. Of course I have to start with my own ─ we just opened a new bar in Gwanghwamun, along the Cheonggyecheon Stream at 149 Seorindong. You can even play PlayStation there. However, if you’re on Jeju Island, definitely take a trip to the Magpie Brewery. Magpie is one of the original crop of craft beer firms in Korea, and, to this day, they make some of the best beers around. I’m a fan of their porter especially.

In Busan, check out Gorilla Brewing. Gorilla is run by a fellow Englishman, and its Dark Nut Brown brown ale is particularly excellent. There are many more though. Hwasoo in Ulsan and Milbat in Gwangju deserve a mention, too, for instance.

Finally diversity in Korean beer has been realized. When I wrote my article, it was about more than just criticizing the blandness of Korea’s big lagers. It was a lament about the lack of choice. Today there are local breweries all over the country and everyone is able to distribute their beer, as long as it tastes good. In a land of constant change, I’m still proud and delighted to have accidentally played a small part in changing one particular field.

Other Articles

Consilience

Application of subscription

Sign upReaders’ Comments

GoThe event winners

Go

September 2018

September 2018